By Lennert Gesterkamp

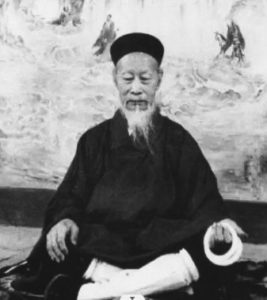

Mr. Schipper was a researcher of Daoist learning and received a Daoist ordination, becoming a fully foreign Daoist priest.

On May 12, 1970, a guest arrived. It was the famous Mr. Schipper. He spoke fluent mandarin (he could also speak Hokkien), and because of his broad knowledge and the many books he had read, he was very engaging.

He said: “The books of Wonderful Publishing House, I read them all. They are all extremely good, but there is one that I like to read the most . . .”

“Which one?” I eagerly asked.

Without thinking for a second, he replied: “Record of Inquiries about the Dao.”

The above encounter is from the publisher’s preface to the Fangdao yulu 訪道語錄 or Record of Inquiries about the Dao. Mr. Schipper is the famous French-Dutch professor and de facto founder of Daoist studies in the West, Kristofer M. Schipper (1934-2021), who conducted field research in Taiwan from 1962 to 1972 and was the first foreigner to be ordained a Daoist priest. The book he praised is essentially a collection of interviews on Daoist self-cultivation techniques conducted by author Li Leqiu 李樂俅 with more than fifty people in Taiwan over a ten-year period in the 1950s. As such, it is a unique repository of orally transmitted knowledge about the esoteric practices of Daoism that is not normally shared with the uninitiated and is even more rarely published. We can therefore understand Schipper’s pleasure in reading this work.

Despite its uniqueness and special place on Schipper’s reading list, the Record of Inquiries about the Dao is, to my knowledge, not mentioned anywhere in his numerous publications. Even more, the esoteric practices of Daoism discussed in the book never seem to have figured prominently in Schipper’s publications. Rather, he is best known for his groundbreaking research on Daoist rituals, local cults, and Daoist texts. His life’s work is The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion to the Daozang, in which he and his team of scholars analyzed, dated, and summarized over 1400 Daoist texts. In fact, esoteric practices or, more precisely, the word “esotericism” are hardly found in Daoist studies as a whole. With the establishment of Daoist studies, Daoism was defined as a Chinese religion in the West as well, a definition that was, of course, heavily dependent on Schipper’s research. According to this view, Daoism and Chinese religion were almost identical and consisted of a society organized into local cults, all linked by a liturgical framework represented and embodied by the Daoist priest and his rituals.

This emphasis on ritual and social organization as hallmarks of Daoism contrasts sharply with what has been happening in China since the beginning of the 20th century, of which the Record of Inquiries about the Dao can be taken as a representative example. With the fall of the last dynasty in 1911 and the establishment of the Republic, Chinese society underwent a series of rigorous reforms aimed at modernizing society and bringing it up to the level of the West. Of course, many reforms were modeled after Western ones, such as the introduction of the new category of “religion” (the Chinese term zongjiao 宗教 was introduced from the Japanese language in the 1890s), and Daoism, like the other “religions,” had to organize itself into a Daoist association and define itself according to Western, Christian criteria. In this definition of Daoism, rituals were almost completely deleted, and everything related to local cults was absent. Rather, the definition of Daoism in China emphasized the kinds of esoteric practices that were discussed in the Record of Inquiries about the Dao. In many cases, these practices were not even considered a “religion” but a “science” because they could be learned and studied by anyone, regardless of their background or beliefs. Moreover, the practices were learned from a master, and in these loosely organized groups, communal rituals, festivals, temples and their images, and the numerous Daoist texts and liturgies played no role. All these aspects are reflected in the interviews of the Record of Inquiries about the Dao.

It follows that we have two almost diametrically opposed conceptions of Daoism, one in China and one in the West, which arose at almost the same time. This, of course, raises the curious question of why they are so different, even though they are both the same Daoist culture? This question will form the basis for a study and a translation of the Record of Inquiries about the Dao I am preparing at the Center of Advanced Studies in Erlangen as part of the project on alternative realities and esoteric practices in a global perspective. The study will hopefully contribute to a better and more comprehensive understanding of Daoism and its practices in East and West.

#

Lennert Gesterkamp is a sinologist and Chinese art historian specializing in Daoist art, ritual, and text, as well as in East-West cultural exchanges. He graduated from Leiden University, and previously was a postdoc researcher at the Academia Sinica, Zhejiang University, and Utrecht University.

__

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by CAS-E on March 3, 2023.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.

__

Image credits: © Chinese Folk Religions website.