by Knut Graw

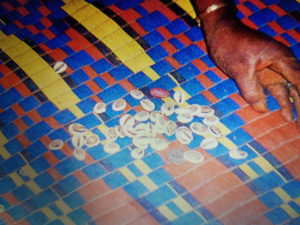

At the end of a long and intricate divination session in a small, secluded room located against the back wall of a larger family compound in Serekunda, one of the large, sprawling suburbs south of the Gambian capital of Banjul, a diviner, specializing in cowrie shell divination, gathers up the shells spread out in front of him one last time, places them in a small pile in front of him, and by leaving them untouched signals to his client that the consultation has come to its end. Considering what he has been told in the course of the session, the client says

̶ Toñaa lom. It is true.

That what you have seen (in the shells),

(that is) what you have said.

The way you said it,

that is the way it will be.

These three sentences express well what divination is about in the Gambia, Senegal, and neighboring West African countries. Divination is a process of “looking at” someone’s situation (ka jubee) by means of cowrie shells or another divination instrument, without knowing what the client is inquiring about. All that is known is that it must be something important, something that is difficult to assess by other means, such as a health condition that defies biomedical diagnosis, or something too difficult to consider without first examining the possible consequences and ritual safeguards, as is often the case with plans for long-term travel or migration. It is a means of seeing (ka jee) what is at the core of a person’s concern. And since diviners are able to see and speak to their clients’ concerns without knowing their exact nature, what is said during the consultation is regularly perceived as true (toñaa).

Witnessing such consultations, the importance attached to them and the dialogic unfolding I have attempted to outline in my lecture, it can only be surprising that the study of divination by anthropologists and others is so often dominated by questions of rationality and method rather than dialogue and hermeneutics. Of course, things have come a long way since Evans-Pritchard’s seminal work on Azande oracles, or William Bascom’s works on Ifa and Sixteen cowries divination, but at the same time I would argue that external descriptions of divinatory traditions are still more common than internal accounts of what is said during divination, and how divinatory dialogues and enunciations are experienced. For this reason I thought it more important to provide examples and excerpts from consultations in my lecture on Divination Dialogues (CAS-E Lecture Series, Erlangen, May 23, 2023) so that the dialogical, hermeneutic, and existential dimensions of divination are not overlooked or glossed over, even if one cannot be present oneself.

At the same time, the recognition of dialogue in divination may not be very revealing as long as it is understood as little more than verbal exchange. Or, as I argued during the lecture, the whole question of the significance of dialogue in divination may be misleading as long as dialogue is considered only from the point of view of how it manifests itself as a situation of verbal exchange (i.e., exhibits dialogic form). Rather, in order to understand the significance of the dialogic dimension in divination, dialogue must be grasped as the expression of the intersubjective, consultational relation between diviner and client. A relation that actually already begins at the moment when the client enters the diviner’s room with the intention to consult the diviner about a personal problem, and when he or she is received by the diviner with the intention to “look at” his or her situation with the help of of divinatory procedure.

Seen in this light, divination becomes a practice of dialogue almost without the need for words. A dialogue without talking in which the focus is not on what can be said, but on recognition and attention to a person’s personal situation, affliction or predicament. And even if certain elements remain fragmentary or are only hinted at, the recognition of the person’s personal concerns nevertheless forms the core of what makes divinatory consultation meaningful as an intersubjective, hermeneutic ritual practice. Whether or not we grew up in a culture with a living tradition of such a practice, perhaps we can all identify with situations in which we feel listened to and truly heard, moments in which what we are struggling with is received and addressed without judgment, and at the end of which we are able to move on and act again. Even though the circumstances themselves may still be there, perhaps unchanged, a new understanding of our situation and new ritual means have emerged that allow us to begin anew in ways we may not have been able to see before listening to the multi-layered messages emerging from the rustling of the shells or from the seemingly opaque signs of geomantic calculations, and perhaps regardless of where and when these signs appear, be it in historical records or in the sprawling neighborhood of Serekunda, south of the Gambian capital of Banjul.

#

Knut Graw is a social and cultural anthropologist specializing in African Studies, ritual analysis and migration theory. He is a permanent research fellow at CAS-E.

___

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by CAS-E on May 12th, 2023.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.

___

Image credits: © Knut Graw