by Keith Edward Cantú

I remember the first time walking up to Sri Sabapathy Lingeshwarar Koil, the temple of Sabapathy as Lord of the Lingam (Sanskrit: Śivaliṅga), or phallic stone that many Hindus worship as the cosmic form of Śiva. Anyone who spends time in south India will soon encounter the postcard-perfect Tamil temples on the pilgrimage or tour circuits, such as the towering medieval stone gopuram gates of Madurai or Thanjavur. The tiny Sabapathy Koil, however, was tucked away down a lane unfrequented by the motor sounds of autorickshaws and ambient foot traffic, opposite to a large, towering concrete apartment building that echoes Soviet-era efficiency. No tourists come here. A dirt road leads off the pavement, adjacent to a much bigger goddess temple filled with large banyan trees. A hand-painted street sign at the mouth of the dirt road reads “Samiyar Tottham”—Garden of the Swamis. I skeptically walk up with two of my three Tamil student friends who generously gave their time to come with me, one as a Christian coming only as far as the gate for religious reasons—could this small shrine be the place?

I am greeted at a wrought iron gate by an elderly man named Hariharan wearing a cream dhoti or wrap with a colorful trim. He opens the gate, which makes a loud clang like a train as it opens on its track to the side. The temple coming into view, I feel an inexplicable rhythm or pulse in my head and chest, buzzing like a bee—“bzzzzz,” the hum striking me as an energetic field created by decades of intense and fervent ritual and meditation. In front of me I see an entry chamber, the floor of which is concrete adorned with white tiles and the walls designating shrines to various gods and goddesses. To the right in the main room was a large, romanticized portrait of an ascetic, the patron of alchemists and the Tamil language, the rishi Agastya with his long black hair in a topknot, and further right a wall consisting of a glass case full of relatively disorganized books. Yet in the center, past the entry chamber, is the main focal point of the shrine—a phallic stone upon which is decorated two eyes, a nose, and a mouth. In front of the stone are yellow marigold flowers, small tools for worshipping with water, and oil lamps hanging from the ceiling. The fragrance of incense, musky and reminiscent of sandalwood, wafts through the air. The eyes of the stone glimmer with a vibrancy and life that would have alarmed even the most hard-hearted skeptic. I knew I had found the place.

What is the place, and who is Sabapathy (Sabhapati Swami, 1828–1923/4)? What kind of yoga did he practice? Before formally starting my research on him in 2015, references were few and far between, but you can now learn more about him in a video here and read my forthcoming book to be published in August with OUP.

I had first read Sabhapati Swami’s name while a teenager in high school, in the literature of the British occult author, poet, and mountain climber Aleister Crowley (1875–1947). I had forgotten all about him, however, and a few prominent Thelemites I knew in the Pacific Northwest encouraged me to look more into his writings once they knew I was studying Sanskrit at the University of Washington. Though they don’t appear to have ever met, Crowley wrote that he encountered Sabhapati Swami’s writings in Madurai in 1901. Crowley made no secret of his appreciation for the swami, and cited him in numerous instances in his literature, including several instructions on yoga and magic published in the journal The Equinox: The Method of Science and Aim of Religion (including “Liber O” and “Liber Astarte”) — for clear scans of these see https://keepsilence.org/the-equinox/. He also utilized Sabhapati’s techniques on canceling the cakras (“Liber Yod”) and envisioning the body as a Śivaliṅga (“Liber HHH: SSS”). While many people think Aleister Crowley and imagine sensationalized claims of black magic, drugs, and sexual promiscuity, even a cursory examination of Thelemic source material reveals a markedly alternative story—it is clear that practices of modern yoga and learned magic(k), and also any use of mind-altering substances or sexual practices, were and are used by most Thelemites for the realization of one’s “true will” and “true nature” as also connected to the good and benefit of humanity. Crowley was also relatively unique for his time in using satirical humor to express anti-Orientalist sentiments and in his emphasis not on romanticizing “Eastern” traditions but recognizing their efficacy where applicable.

My lecture last week for CAS-E highlighted the need for scholarly attention to be given not just to any single religious or philosophical movement, however, but to a broader new typology of yoga, what I call “Modern Occult Yoga” (MOY). This type fits alongside other general types in the study of modern yoga, and especially operates in playful conversation with “Modern Postural Yoga” (MPY), coined by Elizabeth De Michelis. In her chapter (2008) on the history and forms of modern yoga, De Michelis had already insightfully distinguished between at least five types of modern yoga: psychosomatic yoga, neo-Hindu yoga, postural yoga, meditational yoga, and denominational yoga. No mention is made in any of these categories, however, of modern yoga as practiced both historically and presently in what could be termed modern occult milieus. In my lecture I was clear about the fact that “occultism” (from French occultisme), following Strube (2022) and Hanegraaff (2006), was and is not a cohesive movement but rather a “neologism” and porous category that developed in conversation between nineteenth-century French milieus of Spiritualism and Theosophy. Yet as the research of Gordan Djurdjevic and Karl Baier has also demonstrated, numerous authors brought the concept of “occultism” and the “occult sciences”—which dates to at least the sixteenth century—to South Asia from at least the nineteenth century onward.

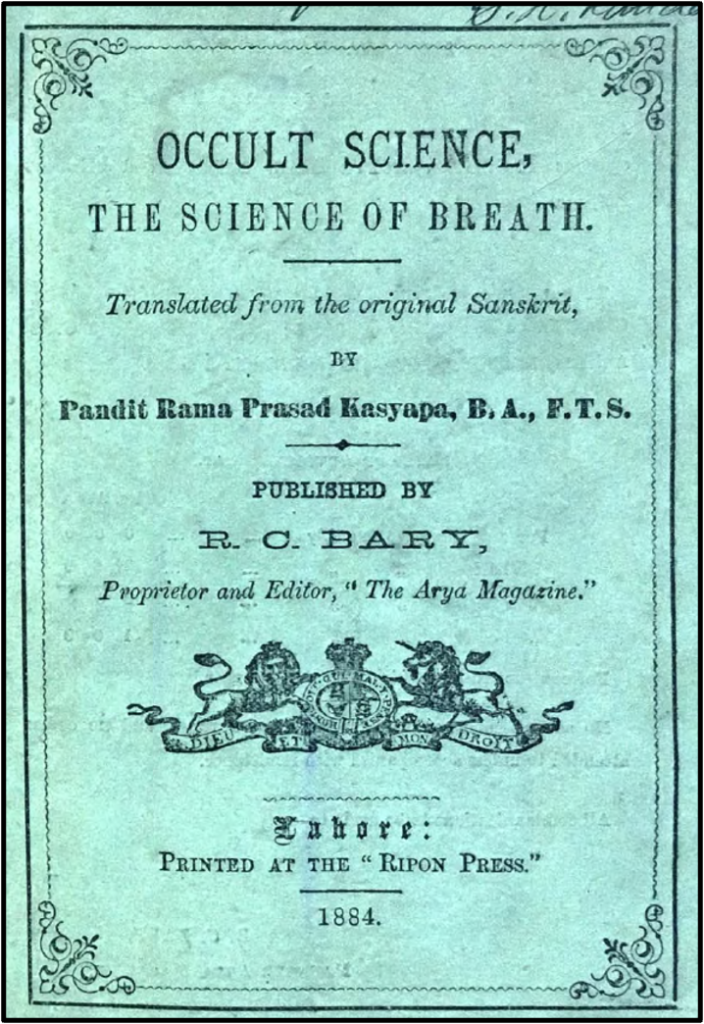

The main logic of positing a separate—yet at times overlapping—type like “Modern Occult Yoga” (MOY) rests on the fact that South Asian authors, notably among them Sri Sabhapati Swami, Shrish Chandra Basu, and Rama Prasad Kashyap (whose writings on the tattvas were integrated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn), and Tallapragada Subba Rao, among many others, used the terms “occultism” and “occult sciences,” alongside similar adjectives like “esoteric,” as emic categories to describe or translate certain techniques or experiences of yoga—these terms were not just used by white Europeans or Americans. While the introduction of these concepts into South Asia seems easy to dismiss as a kind of pizza effect, as coined by Agehananda Bharati (Leopold Fischer, 1932–1921), equally important here are more complex processes like translocalization and transculturation. The local agency of these South Asian authors who are the sources of the global spread of MOY in movements like Theosophy and Thelema are also of critical importance—who were they and what were their interests and motivations? Recognizing their local agency is of key importance to a postcolonial or even decolonizing approach to yoga, as it refuses to treat these authors as mere cogs in a colonial-era web of diluted information. On the contrary, an oft-neglected fact is that many of these South Asian authors—such as Sabhapati Swami and his mantras—were themselves involved in, or had deep connections to, regional forms of yoga that were relatively distant from the colonial project. These forms of yoga gradually appear to have been reformulated into practices that could better suit urban audiences and global interests. As a result, the talk ended with some consideration of how the local/regional/vernacular informed (or did not inform) the global occult and vice-versa—both existed and perhaps still exist in an intriguing dialectic, with Sanskrit, English, and in some cases German and French often mediating. Though the talk ended, I would think that MOY’s discursive life seems to be just beginning.

___

References:

Cantú, Keith Edward. Like a Tree Universally Spread: Sri Sabhapati Swami and Śivarājayoga. Oxford Studies in Western Esotericism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023.

———. “Mantras for Every God and Goddess: Folk Religious Ritual in the Literature of Sabhapati Swami.” In Living Folk Religions, edited by Aaron Ullrey and Sravana Borkataky-Varma. Abingdon: Routledge, 2023.

———. “Sri Sabhapati Swami: The Forgotten Yogi of Western Esotericism.” In The Occult Nineteenth Century: Roots, Developments, and Impact on the Modern World, edited by Lukas Pokorny and Franz Winter, 347–73. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

De Michelis, Elizabeth. “Modern Yoga: History and Forms.” In Yoga in the Modern World: Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Mark Singleton and Jean Byrne, 17–35. Routledge Hindu Studies Series. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J., ed. “Occult/Occultism.” In Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism, 884–89. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

Strube, Julian. Global Tantra: Religion, Science, and Nationalism in Colonial Modernity. AAR Religion Culture and History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

___

#

Keith Edward Cantú is a postdoctoral scholar at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg and a fellow at CAS-E. He is researching South Asian sources for modern occult yoga.

___

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by CAS-E on June 12th, 2023.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.

___

Image credits: © Keith Cantú