By Michael Lackner

The term “esoteric” has no real equivalent in Chinese. For “esoteric Buddhism” and Tantrism, the term mijiao 密教, roughly: “secret doctrine” has become common. Outside of the Buddhist religion, however, esotericism does not exist in Chinese lexicon. The term closest to our Western understanding is shushu 術數, “arts and numbers,” where “number” can often be used in the sense of a cipher, a code for “fate”. Shushu includes primarily techniques of divination, but also physiognomy (mianxiang 面相), palm reading (shouxiang手相), divination by examination of bones (mogu 摸骨), analysis of Chinese characters (cezi 測字), geomancy (fengshui 風水), and name analysis (xingming xue 姓名學). The Treatise on Literature of his History of the Han dynasty, written by historian Ban Gu (32-92), includes categories such as “Heavenly Patterns,” “Calendars,” divination with turtle shells (oracle bones) and yarrow stalks (Classic of Changes, Yijing), and dream interpretation. These categories are essentially computational, but if we are looking for more “esoteric” practices, we must also include techniques based on inspiration (such as from a medium).

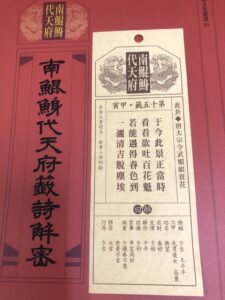

The 2023 “Oracle of the Fate of The Nation” from Nan Kunsheng daitianfu Temple in Tainan, Taiwan

In Taiwan, both forms – which, according to Cicero, can be called “artificial” and “natural” – are still very common today. On their current status, see Stéphanie Homola, “Pursue good fortune and avoid calamity. The practice and status of divination in contemporary Taiwan”; their history in modern China has been reviewed and summarized in detail by Rebecca Nedustop, Superstitious Regimes. Religion and the Policy of Chinese Modernity.

Already the National Party government (Guomindang 國民黨) had issued various bans on practices in the spirit of a Western-defined “enlightenment,” labeling them in a sense esoteric: ”Procedure for the Abolition of Occupations of Divination, Astrology, Physiognomy and Palmistry, Sorcery, and Geomancy’ (1928) , ”Procedure for Banning and Managing Superstitious Objects and Professions’ (1930). When the government had to emigrate to Taiwan after the lost civil war in 1949, this policy was continued, albeit with moderate success: for with the defeated army, numerous experts in divinatory and magical practices also came to Taiwan and spread their techniques, some of which were not (or no longer) familiar to the Taiwanese population after 50 years of “enlightened” Japanese rule.

The Taiwan Social Change Survey, begun in 1984, shows, among other things, that in 2019, 83.1 percent of the population will perform sacrifices to ancestors, and as many as 62.1 percent will observe auspicious/inauspicious days for special activities such as weddings, moves, and funerals. Where could Shmuel Noah Eisenstadt’s concept of “multiple modernities” be better applied? After all, there is no question that Taiwan is a modern state.

Public recognition of traditional practices is even more evident in the phenomenon of the “Oracle on the Nation’s Fate” (guoyun 國運), and here I come to my current research project.

From the abundant data of the Taiwan Social Change Survey, we can conclude that the ground is well prepared for a general recognition of mantic practices. However, since the 1990s, various temples in Taiwan seem to be publicly interrogating the “Fate of the Nation” in their oracle. The very term “nation” signals the choice of Taiwan as a separate nation. But the media, including state television, also report on the various outcomes very intensively. Interestingly, the state television reports in some ways continue a legacy of the earlier “enlightenment campaigns” and still include warnings such as “Folk beliefs. Please do not trust completely” (Minsu xinyang. Qing wu jinxin 民俗信仰。請勿盡信) or “Please do not trust superstitiously” (Qing wu mixin 請勿迷信), although this in no way affects the actual, often enthusiastic reporting.

The oracle comes in two forms: first, the so-called Chinese temple oracle (chouqian 抽籤 or qiuqian求籤 “drawing or beseeching the fortune sticks”); here, people draw one stick from a container of 60 to 100 sticks, each containing an answer and kept in a shrine. These texts contain a poem, a historical allusion and sometimes instructions for daily life. The answers are presented by means of “moon blocks” to the respective temple deity, who can affirm, deny or consider them insignificant. The other variant is so-called “spirit writing” (fuluan 扶鸞 or fuji 扶乩), in which a medium, assisted by a helper, writes messages in a trough filled with sand or ashes at the direction of the temple deity.

Both techniques are centuries old and have been described in detail in research as far as they relate to issues of individuals.

My research project, on the other hand, is concerned with the public, political, and media dimensions of the oracle for the Fate of the Nation: how is it reported and discussed, what issues are taken up? Which topics are in the foreground (e.g., developments in the stock market, the relationship with mainland China, etc.)? Is there retrospective verification of the statements of the various temples, which are definitely in competition with each other? In the meantime, politicians are also increasingly participating in the ceremony (a contribution from TV showed the state president) – can one already speak of a general recognition of such practices (which would imply a shift from “esoteric” to “exoteric) or is the title of my lecture and this article still premature? Have the mantic arts become a feature of Taiwanese identity alongside with democracy and the rule of law, recognition of ethnic minorities, and a multicultural past with the presence of Spaniards, Portuguese, and Dutch?

These and other questions can only be answered through extensive field research. I still have a lot of work to do.

Bibliography:

Banck, Werner: Das chinesische Tempelorakel, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz 1975.

Homola, Stéphanie: “Pursue Good Fortune and Avoid Calamity. The Practice and Status of Divination in Contemporary Taiwan,” Journal of Chinese Religions, 41.2, 124-147, November 2013.

Nedustop, Rebecca: Superstitious Regimes. Religion and the Policy of Chinese Modernity, Cambr./Mass., 2010.

Schumann, Matthias, Elena Valussi (eds.): Communicating with the Gods. Spirit-Writing in Chinese History and Society, Leiden, Brill 2023 (Prognostication in History, vol. 11.)

Taiwan Social Change Survey (台灣社會變遷調查資料庫); respective entries provided by courtesy of Profs. Fansen Wang and Chih-Jou Jay Chen (Academia Sinica).

___

#

Prof. Dr. Michael Lackner is a distinguished sinologist and a senior professor at FAU (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg). He also holds the role of spokesperson at the Center for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences: “Alternative Rationalities and Esoteric Practices in a Global Perspective”

___

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by CAS-E on August 14th, 2023.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.

___