By Monika Hirmer

Tantra has become increasingly popular in Western contexts in recent years, as is shown by the number of Tantra studios, courses, workshops and festivals available across metropoles and towns alike. Roughly dating back to the Counter Cultural movement of the 1960s and ‘70s and its fascination with all things “oriental” and spiritual, this trend is showing no sign of stopping anytime soon. Noticeably, despite its vast diffusion, t Tantra in the West is, thus far, largely neglected within Tantric scholarship. In fact, while occasionally treating the phenomenon in the last chapters of their books, salient researchers on Tantra tantric scholars prefer to focus on Tantra in South Asia; similarly, recent encyclopaedic entries on Tantra dedicate at most one or two sentences to Tantra in the West. Conversely, studies concerning Tantric practices in the West are generally published under separate rubrics, such as New Religious Movements, Esoteric Studies, Gender and Sexuality Studies or Neotantra; a similar division can be observed at conferences, where scholars working on Tantra in the West and scholars studying Tantra in South Asia almost never present at the same panels.

Acts of worship, India

How are we to interpret this dichotomy? Is Tantra as practiced in the West by Western(ised) practitioners, not ‘Tantric’ enough to be legitimately labelled ‘Tantra’? If so, why? And, moreover, according to whose standards?

When looking at the definition, it becomes clear that Tantra cannot easily be described: different scholars, in fact, emphasise different elements as the main characteristics of Tantra, ranging from the importance of gurus, rituals and yantras to the presence of an all-pervasive power, correspondences between the microcosm of practitioners and the macrocosm of deities and the use of so-called impure substances. Overall, scholars agree that a univocal and confined definition of Tantra is untenable and generally opt for a polythetic description. Scholars also agree that ‘Tantra’, understood as a complex philosophical and ritual system, is an Orientalist construct that emerged in the Nineteenth century, which differs greatly from the texts called Tantras. Given the fluid and porous nature of Tantra, the exclusion of Tantric practices in the West from the wider field of Tantric studies needs further investigation.

Offering flowers and a sari to Devī, India

In my anthropological research in India on a contemporary Tantric Śrīvidyā tradition and in my fieldwork in the United Kingdom among Western practitioners, I could observe that, while there are substantial differences, Tantric traditions in the West and in South Asia also have crucial overlaps and similarities. Among the most prominent differences figures the inscription of Western traditions within a neoliberal capitalist framework and of South Asian traditions within the cosmological framework of the Goddess; while practitioners on the one side emphasise individualism and respond to market demands, those on the other side emphasise belonging to their guru’s lineage and respond to divine demands. As my teacher Rajeswaramma aptly says, “South Asians make humans divine, Westerners make Devī [the Goddess] human.” Notwithstanding such discrepancies, it is important to also acknowledge significant similarities; these include the common terminology and symbolism (such as the diagram Śrīcakra), the importance of sexuality (albeit to different degrees) and, most importantly, a life-affirming attitude revolving chiefly around enjoyment.

Tantra Reiki, United Kingdom

Without in any way condoning the commercialisation of rituals or problematic appropriation dynamics, I suggest to revisit the gap that currently separates scholarship on Tantra in South Asia from that on Tantra in the West under the pretext that the latter is ultimately not Tantra. When looking at the history of Tantric studies in South Asia from colonial times onwards, it emerges that what has been considered legitimate Tantra has changed over time, reflecting changing discursive practices around morality and authenticity. At first, the category of ‘Tantra’ was deployed as a colonial tool to differentiate between a supposedly irrational, lascivious and vulgar South Asian spirituality and an allegedly rational, sophisticated and pure Western spirituality; later, with Victorian values fading into the background, Tantric traditions were liberated from the exoticising lens of the Orientalists and became the focus of well-pondered, sympathetic studies. Interestingly, despite the change in approach to Tantra, until recently only ancient texts were considered reliable sources of Tantra, while the experiences of contemporary practitioners were mostly neglected. It is only in the last two decades that anthropological approaches, which revolve around practices and oral traditions, have begun to challenge the notion that ancient texts alone are the repositories of legitimate Tantric traditions. While the preference for texts is still dominant, in recent years important ethnographic studies have contributed to a more complete account of the complex realm of Tantra in South Asia. Furthermore, the praxeological focus has once again shown that Tantric traditions cannot be easily demarcated, as their inherent predisposition to change makes them intermingle with other traditions such as shamanic, folk and pan-Indian ones.

In view of Tantra’s tendency to transform over time and blend with other traditions, the unanimous scholarly acknowledgment that it cannot be clearly defined, and the fact that ‘Tantra’ is ultimately an invented category, one needs to ask whether the current separation between Tantra in South Asia and Tantra in the West is justified and can support an accurate understanding of Tantric practices.

Although my suggestion to revise the field of Tantric studies to include both Tantric practices in South Asia and in the West, rather than treating them as two separate fields, may appear unsettling to some scholars, thus far I encountered a largely positive and encouraging response from CAS-E peers and beyond. In fact, the engaging conversations following my lecture on this topic at the Centre for Advanced Studies seem to support my nascent idea of expanding this study into a larger transcultural project.

#

Monika Hirmer is a research fellow at CAS-E, where she researches tantra from a cross-cultural perspective. Her research lies at the intersection of anthropology and philosophy and spans Goddess traditions, eco-cosmologies and decolonial studies, with a focus on South Asia. In 2020, she co-founded the open access, multilingual and peer reviewed publishing platform Decolonial Subversions.

The research that informed this blog was financed by the Research Network for the Study of Esoteric Practices (www.rensep.org).

___

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on February 22, 2024.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.

___

Image credits

1: Acts of worship, India (Photocredit: author)

2: Offering flowers and a sari to Devī, India (Photocredit: author)

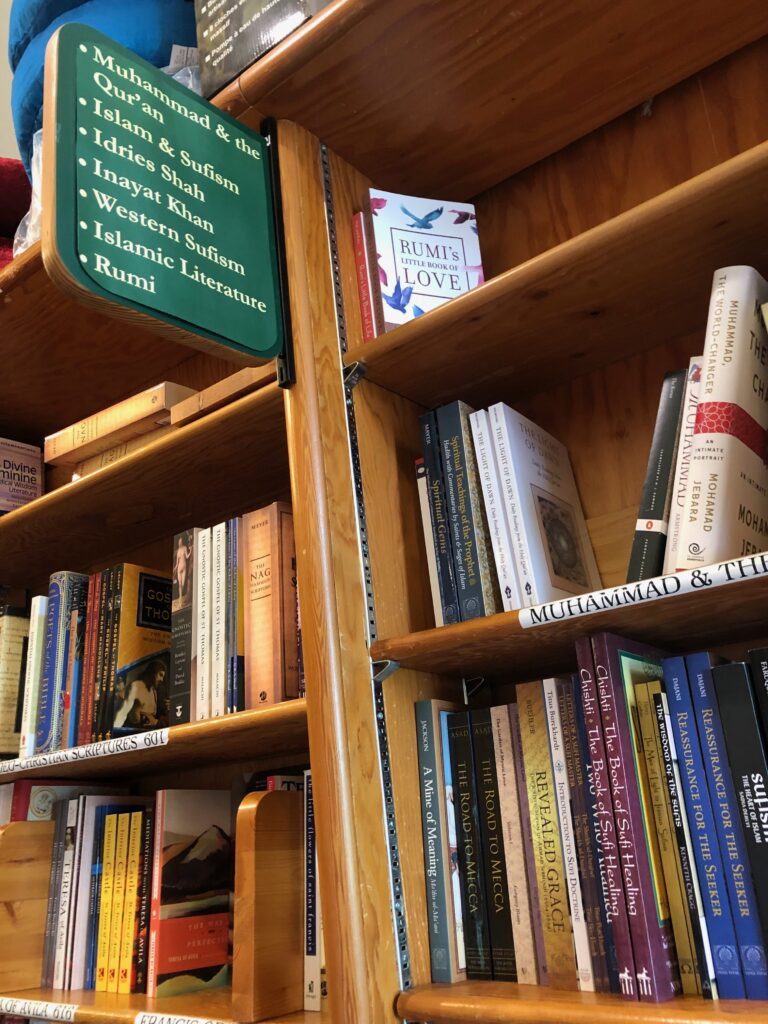

3: Tantra Reiki, United Kingdom (Photocredit: Andy Li)