By Nurul Huda Mohd. Razif

In the last few months of my doctoral fieldwork, after almost a year of conducting ethnographic research on polygyny (one husband, multiple wives) in a few Shari’ah (Islamic) courts around Malaysia, I decided it was time to take my research to an intimate level through participant-observation in a Malay polygynous family’s home. This was how I came to be a resident anthropologist in the home of a first wife in a village in Negeri Sembilan, situated about an hour’s drive from Kuala Lumpur.

Mak Cik – the first wife and my host mother who took me under her wing – lived in a beautiful rumah kampung (Malay traditional house, typically made of wood) that she inherited from her mother through the matrilineal traditions (adat perpatih) unique to this part of peninsular Malaysia. Her co-wife, Mak Nita, lived elsewhere, in another village about 20 kilometers away. In the thirty years or so that they had shared a husband, they never met face-to-face or spoke with one another; it is their husband, Pak Cik, who shuttled between both wives / families in what I call this “multilocal” domestic arrangement.

One hot and humid afternoon, I was sitting in the side porch of Mak Cik’s house with my host sister, Salmah, after a full day of helping with chores around the house. We were savoring the cooling afternoon breeze while enjoying a cup of light but sweet black tea (teh ‘o’) and a plate of banana fritters (pisang goreng). Salmah and I chatted about her childhood growing up with her two sisters in the kampung. Surrounded by tropical greenery, this rumah kampung seemed to me like the most idyllic place to pass one’s childhood – but perhaps I was projecting my own longing for the kampung life, having spent my own younger years in parts of South Asia and West Africa.

Suddenly, a scrawny neighborhood cat jumped into the garden. I asked Salmah if she and her sisters ever kept pets growing up, and she replied, “We tried to – but they never seem to live long.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, puzzled.

“Well, we used to have cats around the house. They always come home with scratches and injuries; some even died mysteriously,” Salmah said. “One morning we woke up to find that all the fish in the tank had died over the night.”

I was intrigued. “What do you think happened?”

“We think the house has a ‘venomous presence’ (rumah ni berbisa). That’s why animals don’t live long around here. We also found strange things around the house – dead birds; black snakes; and once, after heavy pouring rain, we found two chicken eggs in perfect form right here on our doorstep.”

“Where does this ‘venomous presence’ come from?”

“Well…,” Salmah began. After consulting many Islamic healers (ustaz) around Malaysia and Indonesia, she, her mother, and her sisters concluded that these strange occurrences were caused by malevolent supernatural beings (djinns), whose presence, though unseen, could nevertheless affect the health of the house’s inhabitants – both human and animal. Malays believe that djinns may manifest in animal form such as black snakes or scorpions. The apparition of these animals, and the sudden appearance of strange items such as coins, needles, yellow pieces of cloth, and chicken eggs in unlikely places, could mean that the house has been cursed with black magic (sihir) by someone who harbors jealousy or ill-feelings towards the family.

The diagnoses from various ustazes specializing on sihir were quite unanimous, and all pointed to one source: Salmah’s stepmother – her father’s second wife. In the three decades that the two families had become entangled through Pak Cik’s polygynous marriage, Salmah, her mother, and her sisters have had to ward off various supernatural attempts from her stepmother to sabotage her mother’s marriage and their family life. Mak Cik believed that Mak Nita had applied various beauty charms to enhance her own physical appearance to appear seductive to men. She also suspected Mak Nita applied love magic such as pengasih (from the Malay word “kasih” – to love) and penunduk (from “tunduk” – to bow or submit) to make Pak Cik infatuated with her and submit him to her will. No man of good integrity, Mak Cik said to me, would willingly marry a woman who had been divorced “nine times” (her emphasis); some supernatural powers must have been at play. Mak Cik was furthermore convinced that her co-wife had used pemisah (from “pisah” – to separate) to make her and her husband quarrel frequently, feel intense aversion towards one another, and lose all desire for intimacy.

Salmah and her sisters were also not spared from their stepmothers’ supernatural wrath: the ustazes they consulted said they had been cursed with “pelalau” (from “lalau” – to obstruct someone or something), which made them appear unkempt and undesirable to others, such that no (unmarried) man would ever marry them. At nearly 40 years of age, the eldest daughter finally managed to break this curse – but only by marrying a married man as his second wife, thus inadvertently continuing the chain of polygyny in the family.

These accounts of sorcery offer a glimpse into how Malay polygynous families are deeply entangled with one another on multiple levels – emotionally; economically; spiritually. Despite not living under the same roof and having minimal to no interaction with Mak Nita, Mak Cik and her daughters must nevertheless “confront” her presence in their home through the pernicious spiritual emissaries she continuously sent over the years with the help of sorcerers. The anthropologist Peter Geschiere (2003) writes that this is precisely why malevolent supernatural attacks through witchcraft and sorcery represent “the dark side of kinship”: they are often caused by those closest to the victim – discontented kin; jealous relatives; and covetous co-wives. And rampant jealousy, stemming from a perceived socio-economic inequality between those within the community, seems to be the very seed of this evil.

In Malaysia today, sorcery between co-wives especially seems to thrive in an environment of scarcity: male favoritism and unequal access to the husband’s insufficient resources place co-wives as competitors rather than collaborators in the polygynous marriage. Through attacking different facets of the rival family’s life – specifically the home; the hearth; and the heart – sorcery is one way to eliminate competition in the marriage, and to maximize and monopolize access to the husband’s limited resources without any direct confrontation. But sorcery goes far beyond eliminating female competition; it is also a serious assault on Malay womanhood itself. Not only did Mak Cik’s co-wife attempt to sabotage her marriage through supernatural means; she also sent sihir that would have generational consequences by impeding Mak Cik’s daughters from marrying and bearing children themselves – two important rites of passage that define womanhood in Malay society.

The Malaysian state is also implicated in this state of affairs, albeit perhaps unintentionally. In recent decades, the bureaucratization of Islam – and, by consequence, marriage – created legal restrictions in the Islamic family law that made it difficult for men with limited financial wherewithal to obtain approval from the Shari’ah court to marry additional wives. This forced thousands of economically challenged men to contract their polygynous marriage discreetly in Southern Thailand. However, many actually struggle to meet the financial demands of supporting multiple families, forcing co-wives and families to compete for their time, money, and affections. State attempts at gatekeeping polygyny inadvertently made elopements to Southern Thailand more popular than ever, thus allowing unregulated and undeclared polygyny to fester – with dire consequences for women and children (Nurul Huda 2021).

It is therefore unsurprising that polygyny in Malaysia today has acquired an unsavory reputation as a “patriarchal” institution that subjugates women through religious interpretation, male-friendly legislations, and impunitive practices that all favor men’s supposedly “untouchable” right to practice polygyny. As my own decade-long research on Malay polygyny has shown, this reputation is somewhat rightly deserved. But there is also another side to this story that must be acknowledged: much of women’s economic and emotional predicaments in polygyny emerge from insidious forms of intra-female violence that are themselves products of the overarching patriarchal structure that pit women against one another as enemies rather than allies.

While sipping on my cup of teh ‘o’ and listening to Salmah’s stories of their family pets’ premature deaths, I was confronted by the violent and visceral everyday reality of sorcery for this family, and the trail of casualties it left behind. That afternoon, all my earlier romanticization of the quiet kampung life was shattered by the realization that the greatest dangers we face in our lives could come from close circles and unseen sources. Whether separated by distance or dimension, both the natural and the supernatural worlds, and the first and second families, are in fact inseparable from one another and will remain intertwined for as long as they are bound by the polygynous ties that bind them together.

References:

Geschiere, P 2003, “Witchcraft as the Dark Side of Kinship: Dilemmas of Social Security in New Contexts”, Etnofoor, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 43-61.

Nurul Huda Mohd. Razif 2021, “Nikah Express: Malay Polygyny and Marriage-making at the Malaysian–Thai Border”, Asian Studies Review, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 635-655.

#

Nurul Huda Mohd. Razif is a Social Anthropologist and Scholar of Intimacy working on marriage and intimacy in the Malay world and Muslim Southeast Asia. She is currently a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Bergen, Norway. My Marie Curie project, called “MALAYMATRIMONEY” (2024-2026), will study the division of matrimonial wealth in Malay polygynous marriages under the Islamic family law in contemporary Malaysia.

___

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on July 9th, 2024.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.

___

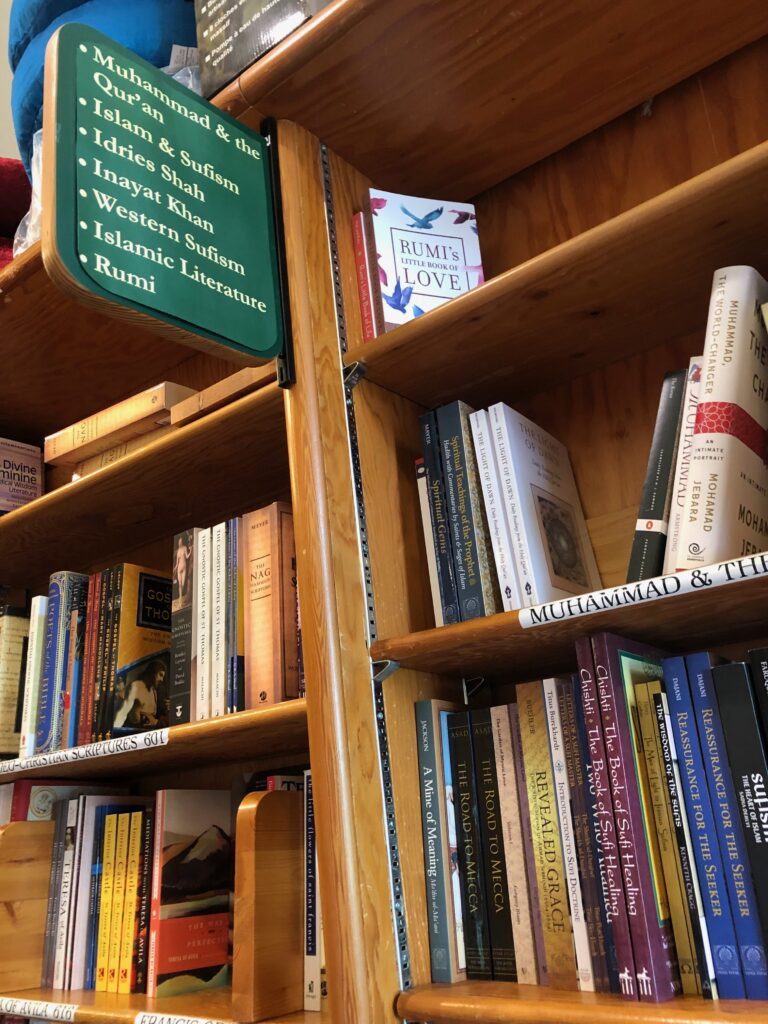

Picture were taken by the author.