By Davide Marino

In 2019, I applied for a PhD at the Chinese University of Hong Kong with a project concerning the influence of Chinese religion (particularly Daoism) on Western Esotericism. During the interview, I recall several objections raised by Chinese sinologists. One in particular struck me: “These authors you want to study knew nothing about the real tradition of China, why should we care about them?” Fortunately for me, in that room was a scholar like Professor James Frankel who, because of his work on Chinese Islam, well understands the subtleties of intercultural exchanges. He accepted me as his student, allowing me to brush off that objection for some time. Nevertheless, that question has continued to follow me even after my doctorate:

“Why should we care about Western Esotericism?”

After all, it is undeniable that the authors included in the canon of Western Esotericism are often highly controversial figures, speaking apodictically about things they often know little or nothing about and, in some cases, using their studies of Eastern traditions to justify disturbing ideologies.1 In attempting to continue answering that question, I sought out scholars in mainland China who have professionally studied the so-called “Western Esotericism.” I was fortunate to meet many of them, focusing particularly on those who dedicated a large part of their careers to translating Western texts—especially given that in China, “academic translation is not only poorly paid; such work is not regarded as an important academic contribution in Chinese universities and research institutions. It is not considered a significant achievement and therefore does not help with professional advancement.”2

In this context, my question seemed to me to become even more relevant: “Why should they care?” There is no simple answer to this question. Unlike what has happened in the West, where the study of esotericism remains very much grounded in the study of (an allegedly “Western”) tradition, in China, those who study material considered “Western Esotericism” do so in constant connection with questions that touch the core of contemporary Chinese identity. As such, “Western Esotericism” is becoming a small but significant part of the mainstream narrative of Chinese intellectual discourse and translations of “Western esoteric” material are used in field as diverse as Sociology, History, Psychology, Philosophy, and even Marxist Studies.

Delving into the world of Chinese intellectuals who study and translate Western Esotericism, I quickly realized that language was the key for entering their intellectual world. Simply put, in Chinese, it is simply impossible to provide a direct translation for words like “esotericism,” “occultism,” “magic,” etc. Or rather, there are countless expressions that indicate “something” in that semantic area, but it is the responsibility (and what a responsibility!) of each author to choose the most appropriate Chinese character to translate terms whose meanings appear highly unstable even in our alphabetic languages.

Taking the term “esotericism” as a simple example, I was able to trace at least a dozen words used to translate it into Chinese, most of which composed with one or more of the following three characters:

- 神 (shén), which can be either a noun (“god(s),” “spirit(s),”) or an adjective (“spiritual,” “divine,” “supernatural,” “magical”). It is composed of the radical 礻 (shì, representing sacrificial offerings on an altar/offering table) and the phonetic component 申 (shēn).

- 秘/密 (mì), both referring to the idea of “secrecy.”

- 灵 (líng), composed of 彐 (jì, phonetic) over 火 (huǒ, “fire”). This character was chosen in the 1950s to replace the previous homophone 靈, made up of 霝 (líng) over 巫 (wū, “sorceress/shaman”). 霝 is composed of 雨 (yǔ, “rain”) over 口口口 (three raindrops), suggesting the meaning of 靈 as “spiritual efficacious,” since ritual specialists danced to call spirits to bring rain. 灵/靈 conveys concepts related to spirituality, intelligence, and the supernatural. As a noun, it can mean “spirit,” “soul,” or “supernatural being.” As an adjective, it implies a sense of spiritual effectiveness

This semantic vagueness made me realize that the issue of translation is crucial to our task to reflect globally on “esotericism.” Instead of attempting to offer an impossible glossary of a supposed standard vocabulary for an equally supposed tradition of “Western Esotericism,” it would be better to try to understand who is translating what, in which way, and why.

Chinese intellectuals are notoriously modest, and I have often heard them lament the backwardness of esoteric studies in China compared to their Western counterparts. From my perspective as a Western scholar, I must disagree with their opinion. While the self-referentiality of the Euro-American academic community of “Western Esotericism” risks condemning the field to self-marginalization and societal irrelevance, Chinese academics, though compelled to contend with an incredible array of linguistic, political, and institutional obstacles, are managing to steer our field of research in new and exciting directions.

As Confucius taught us, “If three walk together, one can be my teacher” (三人行,必有我师). I believe that we Western scholars have much to learn from walking together with Chinese intellectuals.

#

Davide Marino specializes in the interplay between East Asian religions, particularly Chinese traditions, and European Esotericism. His Ph.D. thesis, which received the CUHK Young Scholars Thesis Award in 2023, examined the influence of Chinese and Vietnamese religious concepts on the works of Albert de Pouvourville and René Guénon. More recently, he has been investigating the intersection of politics and esotericism in both China and Europe.

____

Image1: Exploring Western Esotericism: Seminar Insights (by author)

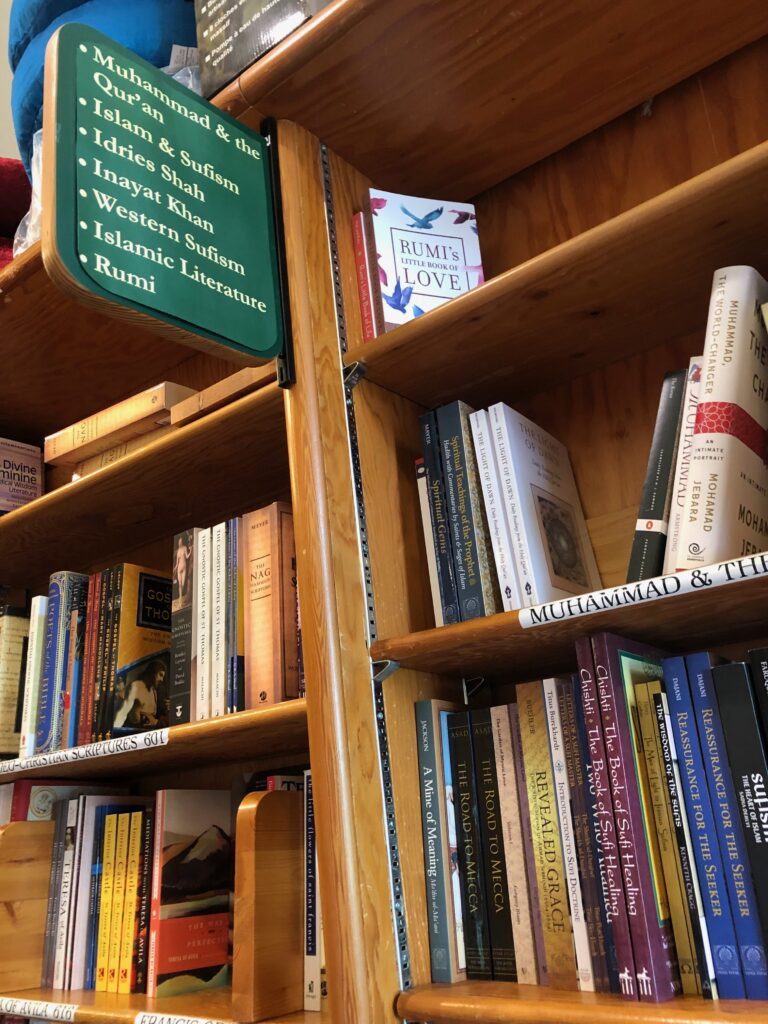

Image 2: Stack of Philosophical and Esoteric Texts (by author)

____

- In my work, I have often showed how occultists have used their speculations about “the Orient” to justify monstrosities such as colonialism and nazi-fascism. See Marino, Davide. “Albert de Pouvourville’s Occultisme Colonial”, Numen 71, 1 (2023): 71-93, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/15685276-20231715; Marino, Davide. “The Tao of Julius Evola”, Vienna Journal of East Asian Studies (published online ahead of print 2024), doi: https://doi.org/10.30965/25217038-01501015 ↩︎

- Zhang Butian, “Translating History of Science Books into Chinese: Why? Which Ones? How?” Isis 109 (4): 784. ↩︎

____

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on December 23rd, 2024.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.