By William Mazzarella

What is it about those bits of writing that grab you? The ones that seem to reach out of a text right in the moment you read them, prompting something like a fascinated shudder of assent. But a particular kind of assent. Not quite assenting to a proposition, but to something more like a possibility. Not knowing what lies that way but certain that it’s going to be important. And that even though you’ve never read these particular words before, in some other sense you’ve always known them.

There is something necessarily idiosyncratic about this phenomenon. You seem to need to return to this passage, to revisit it, explore it, repeat it. You invite others to consider it, certain that it will hit them something like the way it hit you. They indulge you, only to return – at best – expressions of polite perplexity.

But the passage keeps insisting.

Enough of the second person; I should speak for myself.

Sometimes, as I’m writing, that passage moves from being a component of my piece – one among others – to standing out as a sort of key to the whole endeavour. As far as I’m concerned, the passage, just by being there, is loud. It seems almost to be shouting. Perhaps it’s too much; perhaps it’s a bit on the nose.

But when others read my text or hear me give a talk, I realize that most of them, most of the time, don’t even register that passage. In the course of the Q & A after my talk, I don’t even really recognize the version of the talk that my audience is mirroring back to me. That’s only natural; why should they be able to hear the noise in my head?

Let me get specific. For me, one such resonant passage is in fact itself about such resonant passages. How uncanny is that? This passage, ‘theory’ though it might be, actually does what it says.

The words occur in Peter Sloterdijk’s Bubbles:

How can it be that for millions of messages I am a rock on which their waves break without resonance, while certain voices and instructions unlock me and make me tremble as if I were the chosen instrument to render them audible, a medium and mouthpiece simply for their urge to sound? Is there not still a mystery of access to consider here?1

I have a vivid memory of the first time I read this. I was hefting Bubbles around – no small task. It was in the spring of 2015, it was a sunny day, and I was enjoying a solitary reading lunch on the outdoor patio of the Medici restaurant in Hyde Park, just off the University of Chicago campus. I didn’t know it then, but reading Bubbles in conjunction with thinking about my own field research would send me down long and winding esoteric roads. But in that moment on that day, I remember being so excited by these words that I had to struggle to stay seated. I really did feel, suddenly, “as if I were the chosen instrument to render them audible.” The book that I published a couple of years later, The Mana of Mass Society, was the first rendering. (I say ‘the first’ because one is never done with the encounters by which one is unlocked, although one may decide to look elsewhere).

In December 2024, I gave a talk at the invitation of the good people at CAS-E on a book that I am writing. The protagonist of my story is a man, Kersy Katrak, who, in the 1960s and 1970s, epitomized a wave of flamboyant creativity in the Bombay advertising scene. He was also a talented poet, as well as a practicing esotericist. In my book manuscript, I explore the entanglements between these different magics: the magic of mass publicity, the magic of literary aesthetics, and the magic of…well, magic.

The sixteenth century magus-philosopher Giordano Bruno pops up occasionally in my text. Bruno’s techniques of magical binding can, as the historian of religion Ioan Culianu once pointed out, be seen as a kind of precursor of modern techniques of propaganda and publicity. To be sure, the sixteenth century is a long way from the twentieth, the scene of my story, and I might have considered more proximate enchanters. That said, Bruno did figure in the firmament of Theosophical heroes, not least in India. Madame Blavatsky’s chosen heir Annie Besant, a leading light of the Indian Independence movement, was said by some of her associates to be a reincarnation of Bruno. And Kersy Katrak’s closest living spiritual guides were closely engaged in Theosophical exegesis.

One can, in other words, draw genealogical connections. One may also suppose that kinship-by-reincarnation cares little for historicist timelines. But all that is, to me, less important than something that Bruno wrote, and which I quoted in my talk at CAS-E. Here, Bruno moves the focus away from the bonds that the magician might be forging in the world out there (the spells, the ads) and shines a cautionary light back on the magician themselves. He writes, “Be careful not to change yourself from manipulator into the tool of phantasms.”2

Bruno knew what he was talking about. The official hagiographic version of his life that has come down to us portrays him as a proto-Enlightenment martyr for a scientific truth that the religious authorities could not accept. Infamously, he was burned at the stake in Rome in 1600. A closer look reveals, however, that Bruno understood himself as a magician and that whatever drove him back from years of exile and into the arms of the Inquisition, well aware of the dangers, was a phantasm that had very little to do with the abstract pieties of scientific principle. Kersy Katrak’s pursuit of advertising glory surged and crashed spectacularly in the space of a decade; he spent the rest of his life recovering, both materially and spiritually. Unlike Bruno, he survived and even found some measure of serenity. But like Bruno, one could say that Katrak was a magician undone by his own magic.

The warning stands: Be careful not to change yourself from manipulator into the tool of phantasms. But what is it telling us?

(May I risk the third person now? I assure you it’s only an invitation).

For us modern scholars, the pathos of critical academic distance – call it objectivity, call it impartiality – has become a norm. And yet it is a norm that can only be upheld by means of the most peculiar, not to say perverse, pretense: that our whole scholarly lives are not driven by resonances that become palpable precisely in those moments when we encounter “certain voices and instructions that unlock me and make me tremble as if I were the chosen instrument to render them audible.”

Bruno’s be careful, which had demonological and theological implications, is equivalent to our secular, scholarly ideal of critical distance. An ideal that is laboriously pursued, so Sloterdijk puts it, by means of the “comprehensive de-fascination training”3 that comprises our academic education.4 As scholars we are, it seems, supposed to exercise a version of the same vigilance as Bruno’s magician.

We study magic from a desperately sober remove, lashing ourselves to the mast like Odysseus sailing past the Sirens. No discipline has grappled as intimately with the peculiarity of this maneuver as my own, anthropology; we give our method a name as paradoxical as its practice: ‘participant observation.’

It is as if we simultaneously accept and refuse the insight that Robert Wang, scholar of the tarot, conveys:

The problem arises in that to study any aspect of the Mysteries the investigator must himself become part of the system. He must evaluate it from the inside, which may make it appear that he has abrogated investigative objectivity. Today’s academicism does not allow for the acquisition of knowledge through intuition and psychism, an attitude placing it in paradoxical contradiction to a high proportion of those great thinkers [or societies] whom the Humanities [or anthropologists] study and purport to revere. In the Humanities [and the social sciences], the universities have deteriorated into observers of, rather than participants in, the development of man’s creative and intellectual faculties.5

Consider the well-known ancient story, ‘Appointment in Samarra.’

A rich man’s servant thinks he can avoid Death, whom he has glimpsed making a seemingly threatening gesture in a Baghdad market, by fleeing to Samarra. But of course it is – and always was – precisely in Samarra that Death is waiting for him. Death’s threatening gesture was only a start of surprise: why was the servant in Baghdad, when their appointment was in Samarra?

In our anxious flight from the intellectual dangers of fascination, are we not like that rich man’s servant, unknowingly running right into the arms of what we are trying our hardest to avoid?

Once again, Bruno: Be careful not to turn yourself from manipulator into the tool of phantasms. What if the phantasm that threatens us here is not a failure of the “de-fascination training” to which we’ve all been subjected? What if the fatal phantasm is, instead, the tranquilizing mirage of “investigative objectivity”?

This is why that passage, whatever it may be, is so important. The moments, maybe just a handful over the course of a lifetime, of being “unlocked.” Sustaining fidelity to those encounters is the opposite of solipsistic navel-gazing. It is the hard and impersonal work of asking a different kind of methodological question: not what kinds of instruments should I be using? but rather What kind of instrument am I?

That is where the work begins, and that is the place to which it returns.

#

William Mazzarella is the Neukom Family Professor of Anthropology at the University of Chicago. His books include Shoveling Smoke: Advertising and Globalization in Contemporary India (2003), Censorium: Cinema and the Open Edge of Mass Publicity (2013), The Mana of Mass Society (2017) and, with Eric Santner and Aaron Schuster, Sovereignty, Inc: Three Inquires in Politics and Enjoyment (2020). He is currently completing an ethnography/memoir/non-fiction novel called Magnetizer: A Fable of Spirit.

____

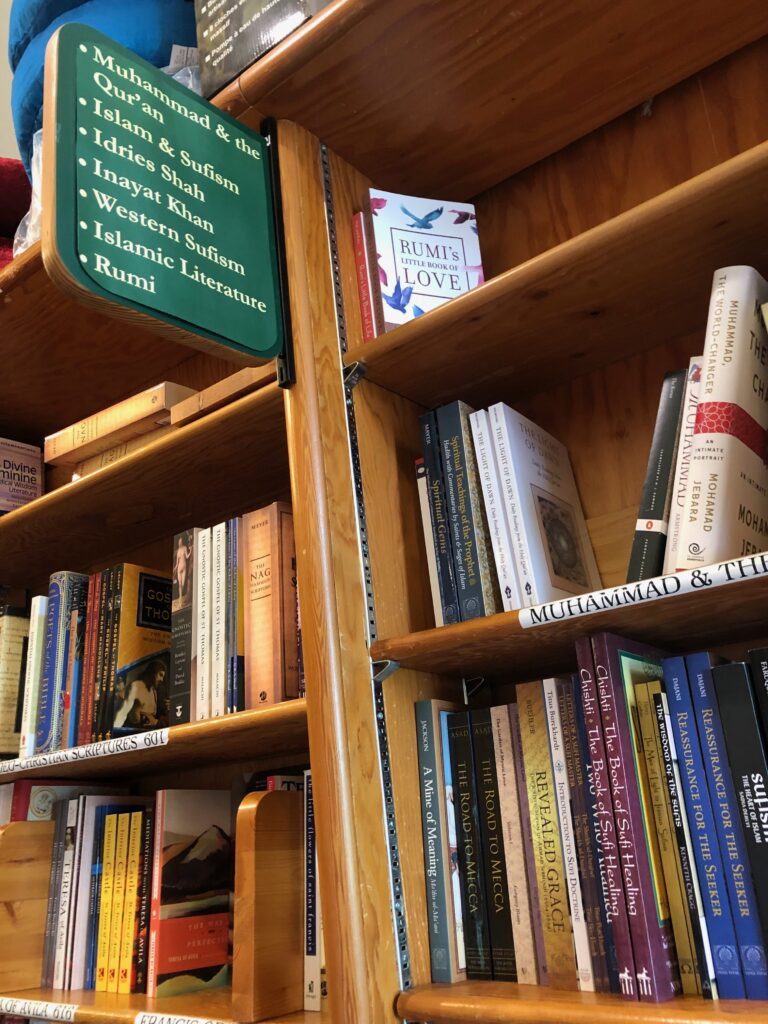

Image1: What Kind of Instrument Am I (by author)

____

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on January 14th, 2025.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.

- Peter Sloterdijk, Spheres Volume 1: Bubbles – Microspherology, New York: Semiotext(e), 2011 [1998], 479. ↩︎

- Giordano Bruno, quoted in Ioan Culianu, Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1987, 92. ↩︎

- Bubbles, 480. ↩︎

- Bubbles, 480. ↩︎

- Robert Wang, Qabalistic Tarot, York Beach, ME: Weiser, 1987 [1983], 4. ↩︎