By M. Shobhana Xavier

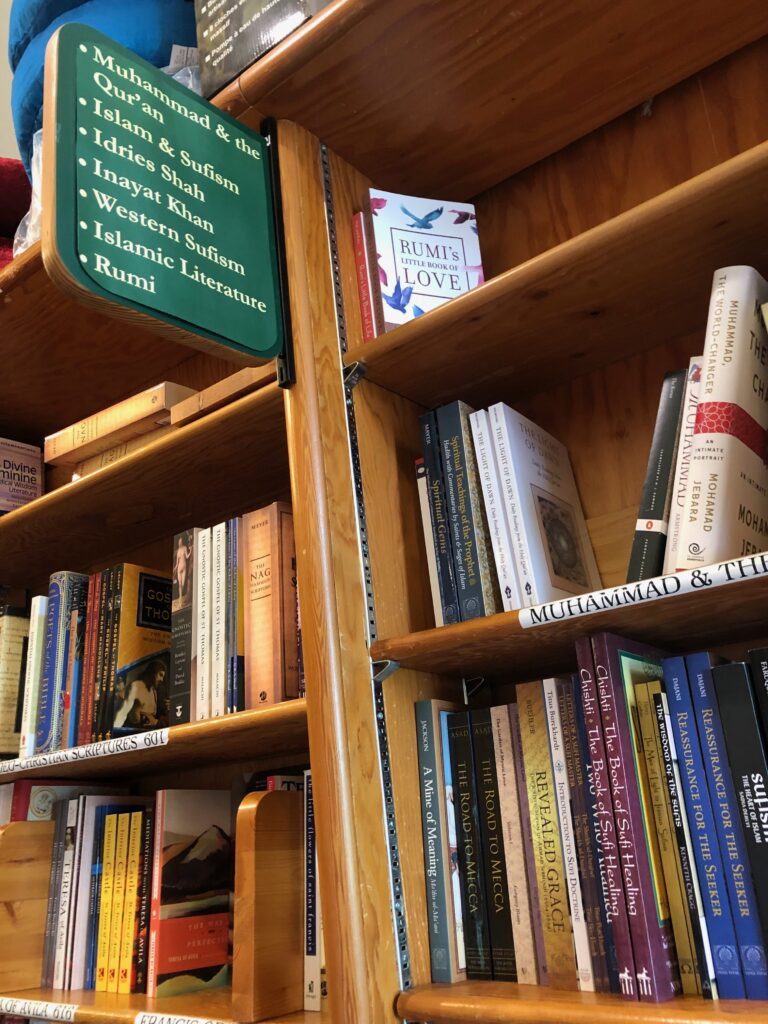

Since my arrival at CAS-E, I’ve been provoked by the question of what is (western) esotericism. It’s been only three weeks for me here at the centre, but my colleagues are thinking about how to frame, deconstruct, problematize, and perhaps reconstruct this label that means many things for the fellows from various disciplines and fields such as anthropology and religious studies. Truthfully, this word has not troubled me too deeply in my own work though it informs the field I write in/for and the worlds my interlocutors practice within (whether they know it or not). In my understanding of Islam, I start from the esoteric threads that informed its early development, especially Neo-Platonism, hermeticism, alchemy, magic, astrology, and much more. These deep and dense fibres have defined philosophical, metaphysical, cosmological, and mystical schools of thought, such as Sufism and Ismaili tradition, which are contained within the capacious and contested umbrella of Islam (though these rarely get the airtime)1. These threads also signal to the networks and cross pollinations that informed the emergence of Islam as a social, political, and religious movement beyond the seventh century Arabia. No idea emerges in a vacuum. Of course, western esoteric traditions have drawn from these threads (in literal and abstract ways) but have interpreted them into their own sets of realities (i.e., borrowing and appropriating from various non-Christian traditions). Perhaps Mark Sedgwick’s scholarship best captures some of these transmissions and translations most clearly for my field of contemporary global Sufism. So, in my own work it is more useful to speak of esotericisms in the plural or on the spectrum instead categorizing through only western esotericism (which overlooks Islamic esotericism in my instance).

Set against these overlapping esotericisms, I’ve been thinking seriously about the lived realities of Sufism in the United States, Canada, and Sri Lanka for well over a decade now. During my lecture at CAS-E, I spoke about some of my initial research in the United States via the shrine of M. R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen (d. 1986) a Tamil teacher who came to Philadelphia, United States in the 1970s and established a transnational community between Sri Lanka and the United States across Sri Lankan and American students (he spoke only in Tamil by the way). His teachings were deeply metaphysical drawing from Islamic and Hindu lexicons and stories and thus was boundary blurring. When he first came to the US he was known as Guru Bawa. The guru was eventually dropped in usage because of the various guru-abuse scandals unfolding in the United States across the American seeker communities and the persistent cult-hysteria during that time. Still, journalists, students, scholars and others tried to label him, Muslim, Sufi, Hindu, spiritual, guru [insert other titles as you please here]. But even he actively evaded all these labels and asked everyone to focus on the ultimate one, the Creator. The desire to index him continues into his death, now he is a saint, a holy one, the Sufi saint of Pennsylvania (the US state where his remains are interred and now a popular American Sufi pilgrimage site)2.

Trying to make sense of all this complexity as a PhD student led me to Sri Lanka. I thought going to Sri Lanka and understanding his original centers in Jaffna and Colombo would help me figure him out, but this only intensified the religious and ethnic diversity I encountered. Now I found Hindu and Muslim followers across Sri Lanka. In an ethno-linguistic and religiously fraught landscape like Sri Lanka, this is quite telling. How did he bring all these different people together in the name of the divine or for spiritual community? And how am I as a religious studies scholar supposed to make sense of this messiness and complexity and communicate it to my readers. This challenge has been one of the defining goals of my academic career. In Sri Lanka, I found more stories of saints like him, at shrines, burial spaces to women and men. Some are long tombs, 40 feet long, descendants of ancient prophets’ others are not dead at all but are immortal like Khidr at Kataragama who visits at a seven-year cycle. These holy beings are timeless, and even spaceless, dwelling in-between realms. So, with imperfect words and sentences I try to make sense of it all.

My favourite part of a lecture are the questions. They signal to resonances, dissonances or even absences, they provoke and interpret what you have said (or perhaps tried to say) maybe even confront. The hybrid nature opened multiple portals to inquiry this time. During questions from the audience in the room, there were sonic interruptions or perhaps better framed here as interventions from Sri Lanka via Zoom. As we scholars sat in the room processing my presentation, trying to think of smart or even relevant questions to ask, some on matters of deconstruction of categories and others on threads woven through the presentation on futurism and embodiment, the reclamation projects of shrines in Sri Lanka amidst a post-war reality, the sonorous virtual voice from a colleague and Zoom audience member from Sri Lanka reminds us that these efforts to understand phenomena, cultures or religions [again insert your disciplinary word here] in the field are not merely intellectual exercises or curiosities that stay within the confines of elite institutions and within the grasp of the limited few with PhDs who are privileged to play and indulge with matters of heart, soul, and mind (as some western esotericists have done before and will continue to do well after we are long gone). Rather the labels we give to spaces, to communities, to peoples, matter. These labels may inform the next path to preservation of a site or the demise of it, for political or national projects or for urban development (the building of a new highway) or as expert reports in the courtrooms3. Our categorical productions do have impacts (and I say this is not for the sake of self-importance or ego). They also may not reflect the lived realities always, as communities themselves are not in agreement with how to label themselves or the meanings they give to the labels. At times, labels change, such as from guru to not using guru for functional purposes. So, I always come back to the question what’s in a name anyway? What work does a label or category do? Who does it include and exclude? We can’t forget to keep asking these questions of our work. I think these interrogations are generative beyond just defining Sufism or esotericism but for most of the work we do religious studies and anthropology. Even though I keep trying to understand Sufism through its varied refractions in the world around me, I know, in true Sufi fashion, no word or set of words will ever perfectly capture that nameless reality.

#

M. Shobhana Xavier is an associate professor of religion and diaspora at Queen’s University. She thinks and writes on contemporary global Sufism.

____

- Liana Saif’s scholarship is an excellent place to start for these Islamic esoteric traditions. ↩︎

- You can find out more on The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship in Sacred Spaces and Transnational Networks in American Sufism: Bawa Muhaiyaddeen and Contemporary Shrine Cultures (2018). ↩︎

- I want to thank my colleague and fellow CAS-E fellow Dr. Steven Engler who shared his experience of the Q&A during my lecture which inspired this piece. ↩︎

____

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on June 03rd, 2025.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.