By Albrecht, Jessica A

“Buddhist psychology” is a naming of a specific understanding of Buddhist teachings (such as mindfulness) and practices (such as meditation) that came up first in the late 19th century. Back then, it was one of the main interests of orientalist scholarship. The most prominent producer of such scholarship in the realm of Buddhism was the Pali Text Society. This society, based in London, aimed at translating Pali Buddhist texts from the Theravada Buddhist tradition into English. To do so, they collaborated with many intellectuals and Buddhist monks (Bhikkhus) from Theravada countries for the translations themselves and to gain more materials otherwise inaccessible to Westerners.

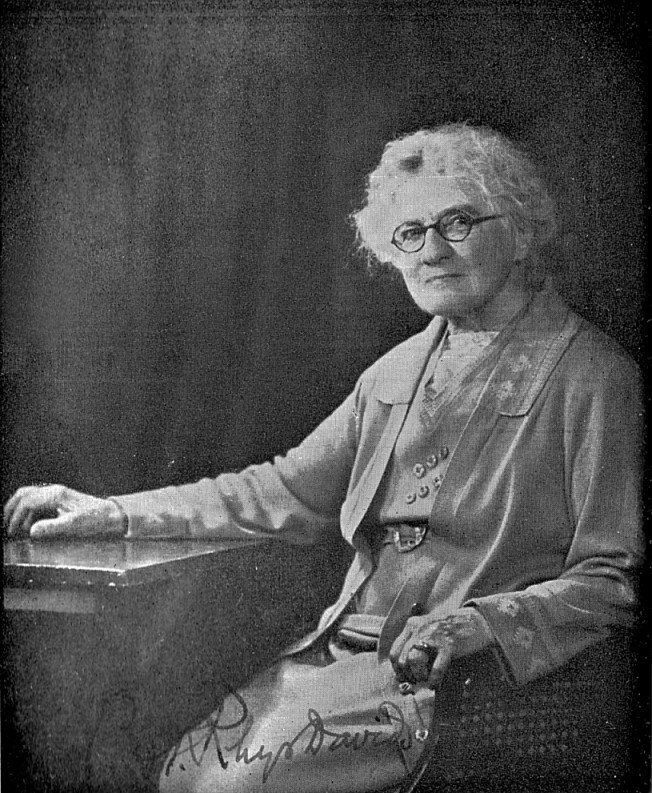

The wife of the first and herself the second president of the Pali Text Society was Caroline Rhys Davids (1857–1942). She became interested in studying Buddhism because she was told that Buddhism offered a unique convergence of her two central interests: psychology and strong female figures. Having had a university education in psychology, Rhys Davids particularly focused on those Pali texts that, according to her, dealt with the psyche, such as the Abhidharma Pitaka. This, she translated with the title A Buddhist Manual of Psychological Ethics (1900).

Her other interest also influenced her perspective on those texts as well as her interpretation of Buddhism more generally. According to Rhys Davids, Buddhist women in the past were emancipated from the societal structures that oppressed them, such as marriage and motherhood, through renunciation and becoming nuns (Bhikkhunis). This was a path also available to women in the present. However, instead of becoming full renunciants, the practice of meditation and the study of the psyche (“psychology”) through Buddhism was the way to go. This was one of the first times in which Buddhist psychology and worldly activism were linked: Buddhist psychology came to be seen as the starting premise from which to develop a practice (mainly meditation) that then could lead to self-emancipation or – as in later renderings within so-called Engaged Buddhism – outward engagement in the world.

Crucially, this understanding of Buddhism as a psychology that, at that time and within orientalist scholarship, specifically focussed on Theravada traditions and the textual study of its teachings, was embedded in a differentiation between science and mysticism (which was later called esotericism). While Theravada and textual scripts were to be studied scientifically (e.g. through philologist methods) as a science (hence, “psychology”), other Buddhist traditions and specifically Tantric traditions such as Tibetan Buddhism were not considered to be “authentic” Buddhism: on the one hand, they were too young to be “original”, on the other hand, they were too practice-based without proper possibilities for textual work.

Consequently, the only practice manual ever translated by the Pali Text Society was called “Manual of a Mystic” (1896 and 1916). The term “mystic”, at that time and in that context, was often applied to practice-based traditions, also in the South and Southeast Asian context. For instance, Tibetan Buddhism was called the “mystic Buddhism”, and this is one of the reasons that people like Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, a founding member and president of the Theosophical Society, became mostly interested in this form of Buddhism – while disregarding the Theravada tradition after a short interest during her stay in Sri Lanka.

From this perspective, it might not come as a surprise that the same tradition that Rhys Davids called “mystic” in Theravada Buddhism, was just recently named “Esoteric Theravada” by Kate Crosby (2020). According to her, the practice was “esoteric” and, thus, hidden, precisely because it was a practice and therefore of no interest to and disregarded by the orientalists.

In other words: esoteric is what is hidden from textual-based knowledge production, because it is a practice that can only be taught directly. The same differentiation can be seen in the 19th century with the word mystic. This relationship between esotericism as practice and non-esoteric as scientific (=text) can illustrate much about the classification practices that the various case studies at CAS-E have shown. For instance, it hints to a relationship between Sufism and Tibetan Buddhism in regards of why both became part of scholarly and popular investigations/definitions of the esoteric.

But what might be even more insightful is the relationship between the esoteric and the practices. Why do we study practices to learn something about esotericism and alternative rationalities from a global perspective? I argue that it most likely has something to do with this history of relating the esoteric to practices in the first place. Furthermore, it might also explain why an interdisciplinary lens is crucial to going beyond the text-based approaches and differentiation of the past.

However, it is at the same time a call for a historically based approach to contemporary phenomena. Asking why we name something in a certain way and what this naming then does to the field that we study is essential to understanding what we are doing in the first place. This goes beyond a historization of the subject of our study and looks at what is excluded and what power this exclusion might hold.

In the case of the early 20th century exclusion of Tibetan/Tantric (and Mahayana) Buddhism from Buddhist psychology because it was a mystical practice, this laid the basis for later alliances between esotericism in the West and global Buddhist activisms in the second half of the 20th century such as the influence of the Dalai Lama and Thich Nhat Than. While both of these were embedded in very local struggles for political and religious autonomy, in Tibet and Vietnam respectively, they were also impactful in many spiritual movements in the USA and Europe. Judging from the history of Buddhist psychology, activism and the differentiation between esotericism and science, practice and text, this impact might, in part, be due to the possibility of alliances between those rendered as “other”: the esoteric, the practice, the “unauthentic”.

____

Further reading:

Crosby, Kate. 2020. Esoteric Theravada. The Story of the Forgotten Meditation Tradition of Southeast Asia. Shambhala Publications.

#

Jessica A. Albrecht is a postdoctoral fellow at FAU Erlangen-Nuremberg, at CAS-E as well as the Department of Religious Studies and Intercultural Theology. She holds a PhD in Religious Studies from the University of Heidelberg.

____

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on August 11th, 2025.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.