Alexander Stark

For a long time, I have been interested in Minangkabau studies. The Minangkabau reside mainly in the Indonesian province of West Sumatra and in the Malaysian state of Negeri Sembilan. With more than seven million people, they are arguably the largest matrilineal society in the world. They have attracted many scholars because their society combines a matrilineal social system with a strong Islamic tradition in everyday life. Interestingly, there are not many publications on their traditional healing system. This was one of the reasons why I began to take an interest in Minangkabau traditional medicine. Another reason was that I witnessed treatment methods myself and realized that many locals still consult traditional healers.

I was fascinated by the variety of healers and healing methods. The usual term for traditional healers is dukun. However, some healers belong to Sufi orders such as the Naqshbandiyyah Khalidiyyah or the Shattariyah. Another type of healer is the so-called orang keturunan. The term is derived from the verb turun, which means “to descend.” An orang keturunan is a medium, allowing spirits and jinn to enter her body. Patients gather around her in order to ask which medicinal plants could be used.

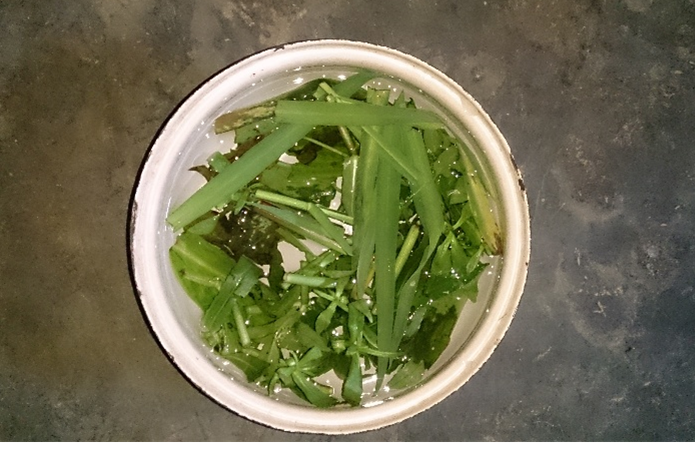

When I first met a dukun, I was staying at the house of a friend when his baby suddenly got fever. His house was quite remote, and so we went to an elderly woman who was a dukun. She examined the baby’s physical condition and prescribed four healing plants, which are called tawa nan ampek. These plants are sidingin, sitawa, sikumpai, and sikaraw. During my later observations, I discovered that these plants function as a connecting element across different Minangkabau healing traditions. All healers were familiar with them and prescribed them particularly for the treatment of keteguran. The term keteguran is derived from the verb tegur and means ‘to reprimand.’ In such cases, jinn are believed to issue a kind of warning. It was assumed that my friend may have worked in a place inhabited by jinn and disturbed them. As a result, the baby developed a fever and my friend was warned to be more careful. The dukun took three leaves of each plant and placed them in a pot of water.

In my further encounters with Minangkabau healers, I repeatedly came across the numbers “three” and “four.” Karl Heider (2011) emphasizes that the Minangkabau tend to categorize elements of their world into groups of three or four. For example, the Minangkabau heartland in the highlands of West Sumatra consists of three regions. At the same time, other aspects of Minangkabau life are subdivided into four categories, such as four ways of speaking to others or four types of knowledge. This form of categorization is part of Minangkabau philosophy. One of its most important maxims is alam terkembang jadi guru – “unfolding nature is a teacher” (Navis, 2015). The four healing plants are part of nature. After they were placed in water, a branch of the saliguri plant was added, and the mixture was sprinkled over the patient’s back. After a few days, my friend’s baby recovered. This experience motivated me to further explore Minangkabau medicine.

In the course of my research, I encountered two general attitudes among healers. Some were reluctant to share their knowledge and told me, “If you write about our healing methods, then we will have no work.” Others were excited and willing to teach. One healer, in particular, regarded me as a kind of student and observed when I was ready to proceed to the next level. At such moments, he would say, “Oh Alex, by the way, there is …,” indicating that he was introducing a new topic. It is this healer’s system that I would like to describe briefly. At the beginning of my research, I assumed that a medical disorder would occur and that the healer would then prescribe medicinal plants. However, I learned that Minangkabau healing is based on three interconnected healing forces.

- Tawa Allah: This element contains doas (supplications) that can be used.

- Tawa Muhammad: There are self-healing elements within the human body. It is called sirr. For the healing process, it must be activated.

- Tawa Bagindo Rasulullah: This element often contains plants.

In some cases, it is necessary to activate all three elements, particularly when supernatural disturbances, such as magic or interference by invisible entities, are involved. Such disorders may require several levels of treatment. For example, if a jinn disturbs a person and possession occurs, the healer may begin by prescribing three medicinal plants—limau kambing, leaves of limau kambing, and jari angau. These ingredients are placed in a bucket of water and poured over the patient’s body. Some healers recite verses from the Qur’an, while others use incantations learned from their teachers.

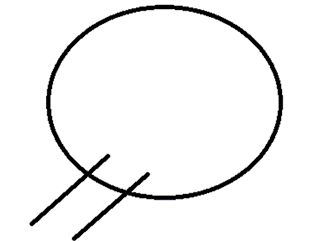

Healers also employ various methods to detect the origin of a disorder. One method involves the use of eggs. After reciting an incantation, the healer may observe patterns that appear on the eggshell. Only the healer and officially initiated students are believed to be able to see these patterns. Nonetheless, the healers have some notes, which could be studied. There is a list of patterns that should appear on the eggshell. An example could be the following pattern:

This pattern indicates that something was placed near the stairs, maybe some magical ingredients. However, there would be no further information. If the healer wants, he can inquire again and break the egg and analyse whether there are patterns on the egg yolk and he would be able to see more patterns. If necessary, the healer may break the egg and examine the yolk to obtain further information. Other forms of divination are also used.

The Minangkabau healing system ultimately reflects a worldview in which balance, belief, and nature are inseparable. It is deeply rooted in the local philosophy, which views nature as integral to healing. Furthermore, the Minangkabau healing system considers local beliefs in invisible entities who can be the cause of some medical disorders. The already mentioned keteguran is a good example. Human beings should not disturb the realm of the jinn. Another example would be the rongeh tree. The sap of this tree can be harmful. In an emic understanding, there is also a jinn that resides in such a tree. If someone goes into the jungle and comes into contact with the sap, that person becomes ill. The skin becomes infected, and the healer will not only prepare a remedy with plants, but he or she also has the task of convincing the jinn not to harm the victim.

Finally, I would like to say that the knowledge of the traditional healing system seems to be endangered. Many healers were quite old and some of them passed away during the period of my research. Only one had a successor who was willing to become a healer. This situation highlights the need for further studies and documentation of traditional medical knowledge.

#

Alexander Stark is an anthropologist with over a decade of experience working in Malaysia. His research focuses primarily on traditional medicine and local wisdom in both Malaysia and Sumatra. In addition to his role as a university lecturer, he actively participates in various qualitative research initiatives across the region. His ethnographic work has taken him to diverse communities, where he explores cultural practices and indigenous knowledge systems. He is also a committed member of several professional bodies, including the Qualitative Research Association of Malaysia, reflecting his strong engagement in the field of qualitative research.

References

- Heider, K. G. (2011). The cultural context of emotion. Folk psychology in West Sumatra. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Navis, Ali A. (2015). Alam terkembang jadi guru. Adat dan kebudayaan Minangkabau. PT Grafika Jaya Sumbar.

____

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on January 29th, 2025.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.