By Douglas Stephen Farrer

Living in Singapore and Malaysia for nine years (1998-2007) I researched Malay mysticism for a doctoral thesis in anthropology at the National University of Singapore (Farrer 2009). Visiting the beautiful gardens of political author S. H. Alattas in Janda Baik, Malaysia, at the fin de siècle, I stumbled across a variant of what Howard Becker (1982) called “art worlds” – the people and institutions involved in the production, exchange, distribution, and consumption of what is considered art. Around a year later, in Singapore, I met Mohammad Din Mohammad (1955-2007), a Sufi fine artist, spirit-healer (pawang/bomoh), and Malay martial arts master (guru silat). Given our mutual interests in silat, witchcraft, and traditional medicine we embarked upon a shared visual anthropology of art. Hence the fieldnotes I complied (in situ from participant observation and digitally recorded in-depth interviews) are illustrated by hundreds of photographs of Mohammad Din’s artworks. Given additional resources by the late artist’s wife, Hamidah Jalil, his diary, correspondence, and a collection of fifty-five newspaper clippings, I have written about cognition and death (deathscapes), agency in healing arts (bomoh art), Sufi war magic (Haqqani-Naqshbandi bodyguards), and dreamwork in miraculous visions (see below) (Farrer 2006, 2009, 2008, 2020). Towards a research capstone, my CAS-E lecture entitled “Dreamcraft in the Malay Art World” introduced the concept of “dreamcraft” to address dreaming (broadly defined) as agentive in the production of art. Reading Mageo and Sherriff’s (2021) edited volume New Directions in the Anthropology of Dreaming I was struck by the idea that dreaming builds culture. Dreamcraft, described below, provides a new direction to explore dreaming as a mechanism in building art worlds.

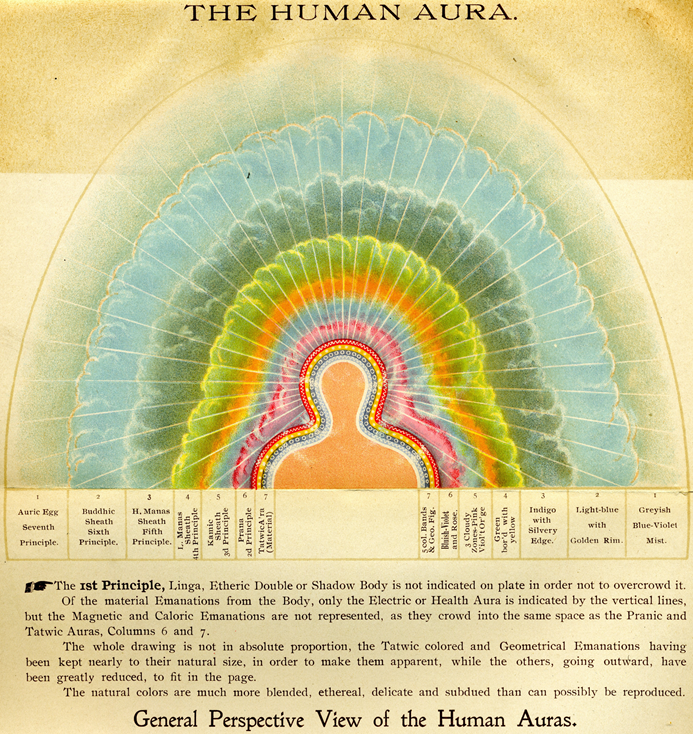

Malay dream-art arises from “spiritual contact” (menurun) similar to what Devereux (1957, 1951) called “dream learning” in night dreams, visions, and trance-dance. Spiritual contact with elemental, animal, and ancestral ghosts that occurs in spirit-mediumship, shamanic encounters, ritual ordeals, and necromantic dance is deemed “witchcraft” by Muslim-Malays (Karim 1984). Nevertheless, artists that are spirit-healers (bomoh) and witch-doctors (pawang) like Mohammad Din regard their art as “divine” because spiritual contact only happens with the blessing of Allah. Occult Islamic art uses prayer, doa, and zikr (silent or aloud, individual and group chants of the ninety-nine names of God) to traverse the unseen realm (‘alam ghaib). The artist sculpted acrylic paint onto the canvas with his bare fingertips, chanting zikr to summon power from the unseen realm. Uncanny artworks produced include finger paintings (for example, Pudding Plant) that change with the light, vivid renditions of Arabic calligraphy, apotropaic jewellery, and curious assemblage sculptures of mythological beasts (fig. 1). Not only is the material culture of dream-art channelled from night dreams and visions, but the ghost-artifacts are designed to trigger altered states of consciousness, visions, and dreams in recipients. Hence dreamcraft is a neologism adopted for the channelling of night dreams and visions into material culture for dream-art to “effect” dreaming in recipients (Fausto 2020; Gell 1998).

Dreamcraft may be defined as the channelling of dream-art in waking dreams or trance to effect or startle “recipients” into alternative ways of perceiving audiovisual images (the index) depicted in artwork (Gell 1998; Price-Williams: 1992). In more general, non-technical terms, dreamcraft is artwork channelled in a trip to make people trip. Now how this “trip” (altered state of embodied consciousness) manifests is a twofold process, because on one side is the artist and on the other the recipient. Gell’s (1998) term “recipient” is preferred to “viewer” not simply because the art is audiovisual, but because it triggers a different way of seeing, a Gestalt shift in those undergoing some heightened emotional experience. Perhaps Malays are more susceptible to the uncanny effects of dream-art as they are reported to suffer from a cultural syndrome, latah, that induces bodily mimicry, echolalia, and obscenity in people triggered by a poke to the ribs? In any case, a prime example of dream-art effects comes from a Malay art collector who kept two “Shadow Warrior” paintings beside her bed (Farrer 2020). One night she heard rattling at the door or window and awoke terrified of a break-in. Suddenly she had a vison or dream that the warrior from one of the paintings leapt down in her defence.

The shadow warrior dream forms the subject of my dreamwork article (Farrer 2020) where I argue a case for potentia (potential) embedded in the artwork and interpret the dream from emic and etic perspectives. Yet dreamwork left me unsatisfied for three reasons: First, in Freud (2010 [1955]) dreamwork is a mechanism in the unconscious to disguise thoughts of sex or death so as not to awaken the sleeper. Yet, in Ian Edgar’s (2016, 1995) anthropology of Islam (following his earlier Jungian views on the caring professions) “dreamwork” becomes the interpretation of dreams by a specialized cultural institution or community. Despite the conceptual drift, dreamwork still operates at the level of representational or interpretive thought. Representation inevitably points somewhere else (to psychology or sociology, the individual or the community) and fails to address the dreaming as the agent. Dreaming as the active agent to effect subjectivity provides a breakthrough in the theory of art and agency because we no longer have to postulate animist spirits (Tylor 1913 [1871]), subjective communication (Benjamin 2014), the skilled revelation of skilled concealment (Taussig 2003), enchanted technologies (Gell 1998), occult attribution (Farrer 2009), or enskillment to dismiss agency as “magical mind dust” (Ingold 2011) to appreciate dreaming in art. A new theory of 4E Cognition helps to illuminate dreamcraft as an affordance of the human brain in the environment. 4E Cognition regards the brain as embodied, embedded, extended, and enacted in the world (Newen, De Bruin, Gallagher 2018; Wynn and Malafouris 2021). Hence dream-art channelled in a waking dream-trance-vison provides a means to address alternative rationality (spiritual contact) as embodied, embedded, extended, and enacted in esoteric practice (dream-art).

In sum, dreamcraft is a psychosocial mechanism for “dreaming” material culture into existence. Dreamcraft is widespread across vast geographical regions and temporal locations to appear in everything from Palaeolithic rock art to recent illustrated volumes on witchcraft esoterica (Clottes 20216; Hundley and Grossman 2022). Dreamcraft provides a new direction for research on alternative rationalities and esoteric practices hitherto conducted under the auspices of animism, magic, religion, witchcraft, spirit-mediumship, and shamanism.

Finally, I want to express a note of appreciation for the research faculty and staff at CAS-E. In particular, I am grateful to Michael Taussig, Michael Lackner, Erhard Schuettpelz, Knut Graw, and Emily Selove for commenting on the drafts.

#

Douglas Farrer is a social anthropologist with interests spanning visual anthropology, narrative criminology, martial arts, and performance studies. Based upon fieldwork in Singapore and Malaysia with artists, Sufi mystics, and traditional healers (bomoh) his research focus at CAS-E is on ‘dreamcraft:’ cognition embodied through lucid dreams/trance in divine Islamic art and witchcraft.

____

Bibliography

- Becker, Howard S. 1982. Art worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2014. Temiar religion, 1964-2012: Enchantment, disenchantment and re-enchantment in Malaysia’s uplands. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Clottes, Jean. 2016. What is Palaeolithic art: Cave paintings and the dawn of human creativity, trans. Oliver Y. Martin and Robert D. Martin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Devereux, George. 1951. Reality and dream: psychotherapy of a Plains Indian. New York: International Universities Press.

- Devereux, George. 1957. “Dream learning and individual ritual differences in Mohave shamanism.” American Anthropologist, 59(6): 1036-1045.

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and agency: An anthropological theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Edgar, Iain, R. 1995. Dreamwork, anthropology and the caring professions: A cultural approach to dreamwork. Aldershot: Avebury.

- Edgar, Iain, R. 2016. The dream in Islam: from Qur’anic tradition to jihadist inspiration. New York: Berghahn.

- Farrer, D. S. 2006. “Deathscapes of the Malay martial artist.” Social Analysis. Special edition on Noble Death, 50 (1):25–50.

- Farrer, D. S. 2009. Shadows of the prophet: martial arts and Sufi mysticism. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Farrer, D. S. 2008. “The Healing Arts of the Malay Mystic.” Visual Anthropological Review, 24 (1):29–46.

- Farrer, D. 2020. “Dreamwork, art worlds and miracles in Malaysia.” World Art, 10(1): 25-54.

- Fausto, Carlos. 2020. Art effects: image, agency, and ritual in Amazonia, trans. David Rogers. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln.

- Freud, Sigmund. 2010 [1955]. The interpretation of dreams: the complete and definitive text, trans. James Strachey. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Hundley, Jessica, Pam Grossman, eds. 2022. Witchcraft: The library of esoterica, illustrated by Thunderwing. Cologne, Germany: Taschen.

- Karim, Wazir-Jahan. 1984. “Malay midwives and witches.” Soc. Sci. Med., 18(2): 159-166.

- Mageo, Jeannette, and Robin E. Sheriff, eds. 2021. New directions in the anthropology of dreaming. New York: Routledge.

- Newen, Albert, Leon De Bruin, Shaun Gallagher, eds. 2018. “4E Cognition: historical roots, key concepts, and central issues.” Pp. 3-16 in eds. Albert Newen et al, The Oxford handbook of 4E cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Price-Williams, Douglass. 1992. “The waking dream in ethnographic perspective.” Pp, 246-262 in ed. Barbara Tedlock, Dreaming: anthropological and psychological interpretations. Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of American Research Press.

- Taussig, Michael T. 2003. “Viscerality, faith and skepticism: Another theory of magic.” Pp. 272–306 in Magic and modernity: Interfaces of revelation and concealment, eds. Birgit Meyer and Peter Pels. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Tylor, Edward Burnett. 1913 [1871]. Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art and Custom. Murray: London.

- Wynn, T, Overmann KA, Malafouris L. 2021. 4E cognition in the Lower Palaeolithic. Adaptive Behaviours, 29(2): 99-106.

____

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on May 14th, 2025.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.