Lili Di Puppo

During my July talk at CAS-E, I presented initial reflections on what I call “the vertical dimension of knowledge.” This perspective, which I developed together with my colleague Fabio Vicini in the introduction to our 2024 special section Muslim Ontologies: Divine Presence, Anthropology, and Transcendence (Vicini and Di Puppo 2024, HAU – Journal of Ethnographic Theory), draws inspiration from my field research in Sufi circles in two primary locations: Brussels, Belgium, and Bashkortostan in Russia’s Urals.

In my talk, I reflected on the nature of knowledge, its limits, and the various forms it takes, emphasizing the kind of experiential knowledge I encountered during my field research. For a long time, I have been intrigued by the question of why entire dimensions of human experience and reality appear to be excluded from what academia regards as legitimate knowledge—knowledge that is limited to what is empirically observable. What of the experiences I encountered during my fieldwork, for example, the experience of being lifted up during a ritual ceremony in a small mosque in the Volga-Ural region (Di Puppo 2021) or profound dreams following pilgrimages to saints’ graves? Some of these experiences, which took me by surprise, challenge the limits of academic knowledge, as they cannot fit into conventional analytical frameworks. These moments imposed their presence during my research, revealing how the boundaries of knowing expand precisely when confronted with the limits of what I can describe and analyze. The limits of knowledge—and the spaces that open up when we encounter them—have been a recurring theme in discussions with other fellows at CAS-E throughout the summer semester. How can we make room in our research for such experiences? Does knowledge need to remain confined to what is empirically verifiable? What is the “real”?

Against this backdrop, my talk addressed two central questions that guide my current project at CAS-E: How do Muslims in Belgium and France perceive and respond to potential threats to humanity? And how can these “existential risks” be approached from the perspective of the Islamic knowledge tradition? In my current research, I establish a dialogue between the Islamic knowledge tradition—particularly Islamic philosophy and Sufi metaphysics—and contemporary scholarly fields such as posthumanism, transhumanism, and existential risk studies. These fields all ask the question: What is a human being?

So far, my field research reveals that many of my Sufi interlocutors connect their reflections on contemporary threats precisely with this question: What is a human being? What is human nature, and what is the self? For them, responses to the threats facing humanity today are not to be found in technological advancements, as proposed by scholars writing on existential risk like analytical philosopher Nick Bostrom, but in the “inner dimension” of the human. According to my interlocutors, the way humans relate to the world, creation, and the environment reflects the degree to which they are connected to the Divine (Di Puppo 2024). By experiencing the world and its many beings as God’s creation, humans can assume their responsibility of care toward these beings. Perceiving the world as God’s creation also entails acknowledging human beings’ inherent fragility—their dependence on God and the limits of their ability to control the world and reality.

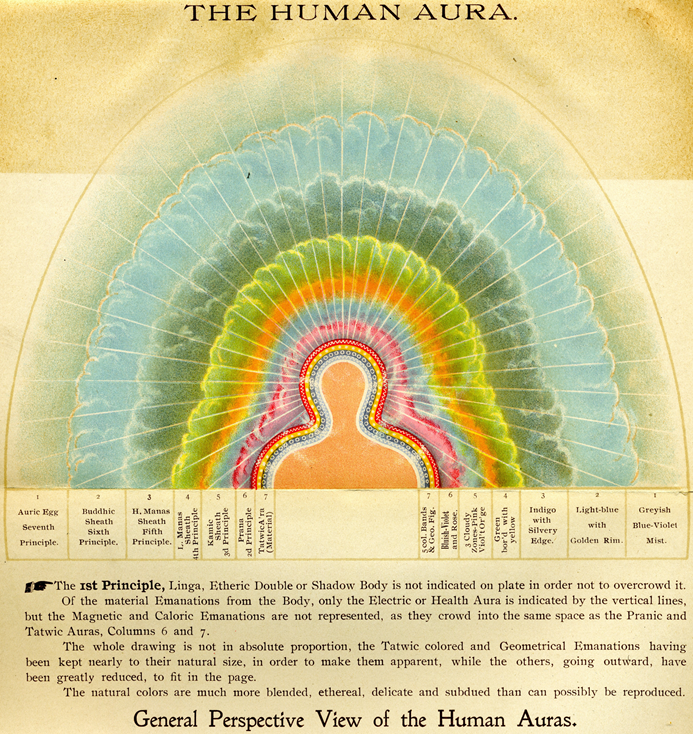

This Sufi perspective on the human resonates with posthumanism, a field that seeks to “dethrone” the human subject by showing how claims of “human superiority” have contributed to contemporary crises, such as the ecological disaster. This aspiration to “dethrone” the human subject finds echoes in the Sufi spiritual path. In the Sufi tradition, the disciple seeks to tame the nafs—the lower self or ego. While posthumanism rejects “verticality” by denying any human superiority over other beings, the process of taming the nafs is, however, akin to an “elevation,” as one Bashkir Sufi interlocutor shared with me. In my talk, I developed the idea that by bowing before God, the human being “ascends,” and this elevation is one of knowledge. As one Belgian interlocutor told me, there are different levels of knowledge, and these levels bring one closer to the state of the human who is in connection with the Divine. However, elevating in knowledge also means encountering limits—the limits of what one knows and the reality one inhabits. It means opening to the Divine and realizing our helplessness.

The questions that emerged from my summer semester at CAS-E, which I plan to continue exploring, concern the dimension of verticality and its significance for my Sufi interlocutors. From a Sufi perspective, freedom is found in the process of taming the nafs, which, as I have noted, is akin to an elevation. This elevation means being drawn toward the spiritual dimension of existence and the realm of eternity, even as the physical world—God’s creation—invites contemplation. In this sense, freedom is not found in a “flat world” devoid of hierarchies, a flatness emphasized by posthumanism, but rather in the process of elevation, a process that centers on “dethroning” the human ego. In the context of the spiritual process of taming the nafs, the vertical dimension is dynamic and not centered on human power, for it is precisely by acknowledging one’s helplessness and bowing before God that one ascends in knowledge. In my future work, I will continue to reflect on the vertical dimension of human freedom and knowledge, exploring what it reveals about reality, its invisible dimensions, and the relationship between humans and the world.

#

Lili Di Puppo is a research associate in the project “Muslims, the Secular, and Existential Risk” at the University of Glasgow, UK, and a postdoctoral researcher at KU Leuven, Belgium. Her research focuses on the anthropology of religion, anthropology-theology, existential risks, sacred sites and human-nature relations. She has conducted fieldwork in Belgium, Russia’s Volga-Ural region, Moscow and Georgia. She was an assistant professor of sociology at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow from 2013 to 2022 and a senior researcher at the Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki, in 2023-2024. She has published a special issue on Muslim ontologies, transcendence and anthropology in HAU – Journal of Ethnographic Theory and two others on Islam in Russia in Ethnicities and Contemporary Islam. She is the convenor of the European Association of Social Anthropology’s network ‘Muslim Worlds’ and co-editor of the book ‘Peripheral Methodologies: Unlearning, Not-Knowing and Ethnographic Limits’ (Routledge, 2021).

References:

- Di Puppo, Lili. 2024. “Between Remembrance and Forgetfulness: Heart Perception, Oneness and the Human-Landscape Relationship in a Bashkir Sufi Circle.” Globalizations 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2024.2383012

- Di Puppo, Lili. 2021. “At the Core, Beyond Reach: Sufism and Words Flying Away in the Field.” In Peripheral Methodologies: Unlearning, Not-knowing and Ethnographic Limits, edited by Francisco Martinez, Lili Di Puppo and Martin Demant Frederiksen. London and New York: Routledge.

- Vicini, Fabio and Lili Di Puppo. 2024. “Rethinking the Anthropological Enterprise in Light of Muslim Ontologies: Secular vestiges, Spiritual Epistemologies, Vertical Knowledge.” HAU – Journal of Ethnographic Theory 14(1): 7-18.

____

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on September 15th, 2025.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.