Oleg Yarosh

My individual research is associated with the CAS-E project Alternative Rationalities and Esoteric Practices from a Global Perspective funded by the DFG. The research investigates spiritual practices within Western Sufi communities, focusing particularly on practitioners’ perspectives – both those of community leaders and ordinary members. It examines ‘traditional practices,’ understood as those embedded within Sufism and Islam as a discursive tradition, as well as ‘entangled practices’ that emerge at the intersection of multiple spiritual lineages. This project builds upon my earlier research exploring conversion to Islam and the dynamics of charismatic authority within Western Sufi communities. Drawing upon an ethnographic study of the Naqshbandiyya-Ḥaqqāniyya and Burhāniyya communities in Berlin, this study demonstrates how power relations in Western Sufi communities, informed by charismatic agency, impact conversions, social relations, and the spiritual practices of their members (Yarosh 2018).

Sufism is currently represented in the West by a broad spectrum of communities, some with a global reach, that range from those rooted in Muslim diasporic groups to non-Islamic communities composed predominantly of Western spiritual seekers. My research focuses particularly on communities that occupy the space between these two extremes. It is in this intermediary space that processes of cultural and epistemological hybridization (Piraino 2024) become most visible, shaping both the discourses and practices of Western Sufis and giving rise to entangled practices. Geographically, my project is situated in Western Europe, with a particular focus on Germany, where a wide variety of Sufi communities of different origins and affiliations are currently active.

Spiritual practices historically employed by Sufi wayfarers across the Islamicate world began to travel Westward with figures such as the Indian Sufi teacher Inayat Khan (1882–1927), whose mission initiated a process of contextualization and hybridization. Within the Western Sufi milieu, a range of entangled practices has since developed, such as breathwork, meditation techniques, and various healing practices that draw on diverse spiritual traditions beyond Islam. These practices, often tailored for contemporary Western seekers, exemplify the adaptive and entangled nature of Sufism as it takes root in a new cultural context.

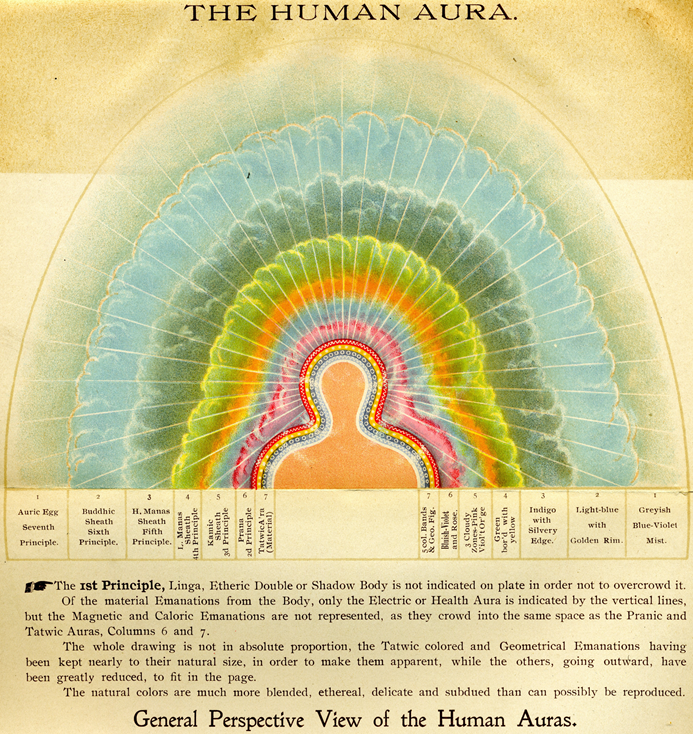

My research examines explicitly transformative-contemplative Sufi practices as methodologies aimed at awakening deeper levels of consciousness and aligning the self with the Divine Reality, through insights cultivated and tested within the Sufi tradition (Buehler 2016). Classical Sufi texts often describe the tradition as a ‘science of spiritual stations and states,’ and this spiritual cartography continues to guide contemporary Western practitioners, while being adapted to local contexts. These transformative practices facilitate the integration of physical, psychological, and spiritual dimensions of human beings, ultimately seeking reconciliation with the Divine. While these practices are primarily oriented toward transcendence, they are not ivory tower exercises in mysticism and also exert significant influence on practitioners’ well-being, social relations, and ethical dispositions.

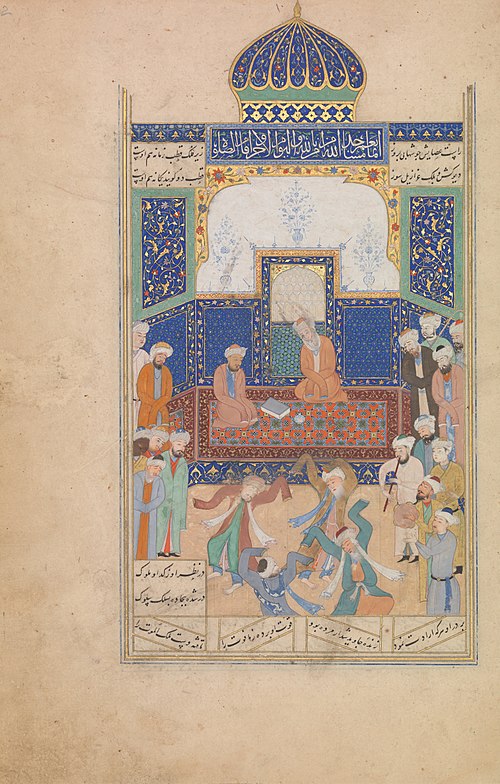

Sufi communities represent a form of redemptive sociality, that is, collective solidarity grounded in allegiance to a charismatic Sufi Shaykh (Werbner 2001). My earlier ethnographic research on several Western Sufi communities indicates that, in this context, Sufi practices function simultaneously as mechanisms of social inclusion and exclusion. The accessibility of these practices within the Western Sufi context varies from one group to another and is shaped by the specific form they take as well as by the legitimizing discourses and authorities that inform them. These factors create distinct esoteric/exoteric regimes and initiatory hierarchies in Sufi communities.

Moreover, such practices often serve as tools of proselytization, attracting new Western seekers, many of whom are already familiar with other spiritual traditions and practices. In some communities, these practices involve a reinterpretation of Sufi rituals through the lens of religious universalism, blending elements of Sufism with diverse spiritual traditions. Other groups offer novices a foretaste of the spiritual destination early in their journey, with the understanding that the deeper reality of these experiences will only be fully grasped at a later stage. In practice, this often includes psychophysical exercises designed to induce ecstatic states of varying intensity, which function as powerful means of attracting new followers. The accessibility of Sufi practices to non-Muslim western seekers, particularly within the intermediary space discussed earlier, not only enlarges participation and followership but may also hinder or postpone the seekers’ formal conversion to Islam.

The global resurgence of fundamentalist Islam parallels comparable developments within Western Sufism, which in recent decades is increasingly adopting Islamic discourses, practices, and community structures (Sedgwick 2019, Dickson and Xavier 2019). This shift enables Sufi communities to build bridges with other Muslim groups in the West, while continuing to maintain a public image associated with tolerance, pluralism, and societal integration, qualities for which they are widely recognized and accepted in the West. My research further investigates the contextualization of Sufi practices in light of both the global rise of Islamic fundamentalism and the ongoing re-Islamization of Sufism.

My research subject closely aligns with key issues of the CAS-E project, namely ‘esoteric’, ‘practices’, and ‘global perspective’. Being a global phenomenon in the pre-modern Islamicate world (Green 2012), in the past hundred years, Sufism crossed its borders, becoming a visible element of the religious landscape in the West. Based on my previous research, I argue that in Western Sufi communities, spiritual experience rooted in the performance of specific practices is regarded as equally important as, or even prioritized over, religious knowledge and conduct. The current project will explore how practitioners evaluate and rationalize the effects of these practices on their spiritual growth, community engagement, and personal well-being. It will also examine how they perceive the balance between their own effort and supernatural agency in the context of spiritual practices.

Current debates on the relationship between Sufism and Islamic esotericism tend to revolve around concepts such as the outer and inner, absolute and rejected knowledge, secrecy, most often situated within an etic framework. This project instead seeks to introduce an emic perspective into this discourse by examining how the categories of ‘esoteric’ and ‘exoteric’, along with their local equivalents, are negotiated within Western Sufi communities concerning spiritual practices. In doing so, my research will contribute to ongoing academic debates on the strengths and limitations of non-essentialist approaches to the comparative study of global esotericism.

I was glad to present my research project at CAS-E and get feedback from colleagues there. It helped me to reconsider some of my initial theoretical premises, such as the taxonomy of Sufi communities in the West and a better understanding of how esoteric practices travel in the global world.

#

Oleg Yarosh, PhD, is an associate professor and former senior researcher at the Institute of Philosophy of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Kyiv and, most recently, completed a two-year postdoctoral position at Aarhus University in Denmark. He is currently an associated scholar at the Center for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences Alternative Rationalities and Esoteric Practices from a Global Perspective (CAS-E) at Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany. His research focuses on Sufism in the West and Muslim minorities in Ukraine and Central-Eastern Europe. His recent papers address post-tariqa Sufism “The Vision of Spiritual Perfection in Shaykh Fadhlalla Haeri and Post-Tariqa Sufism in Western Europe”. Journal of Muslims in Europe, 13 (3), 2024 and post-Islamist ideologies and activism “Negotiating Wasatiyyah: Soft Securitization and Civic Activism in Ukraine”. Religions 2025, 16 (1).

____

References:

- Buehler, Arthur F. Recognizing Sufism: Contemplation in the Islamic Tradition. London: I.B. Tauris, 2016.

- Dickson, William Rory, and Merin Shobhana Xavier. “Disordering and Reordering Sufism: North American Sufi Teachers and the Tariqa Model.” In Global Sufism: Boundaries, Structures, and Politics, edited by Francesco Piraino and Mark Sedgwick, 137–56. London: Hurst, 2019.

- Green, Nile. Sufism: A Global History. Oakland: University of California Press, 2012.

- Piraino, Francesco. Sufism in Europe: Islam, Esotericism and the New Age. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2024.

- Sedgwick, Mark. “The Islamization of Western Sufism after the Early New Age.” In Global Sufism: Boundaries, Narratives and Practices, edited by Francesco Piraino and Mark Sedgwick, 35–54. London: Hurst, 2019.

- Werbner, Pnina. “Murids of the Saint: Occupational Guilds and Redemptive Sociality.” In Muslim Traditions and Modern Techniques of Power, edited by Alessandro Salvatore, 265–289. Münster: Lit, 2001.

- Yarosh, Oleg. “Religious Authority and Conversions in Berlin’s Sufi Communities.” In Moving In and Out of Islam, edited by Karin van Nieuwkerk, 179–203. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018.

____

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgment: “This article was published by CAS-E on September 15th, 2025.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.