By Aleksandrs Simons

My research and deep interest into the religion of the Yi minority in China started in the spring of 2014, simply after reading a single word “Bimoism”when deciding upon my BA research topic. At the time there was almost no available information on this religious practice in the western languages, the sole exception was the work Comme le sel, je suis le cours de l’eau. Le chamanisme à écriture des Yi du Yunnan (Chine) by a French ethnologist Aurélie Névot, which served and still serves as a great influence and inspiration for my research.

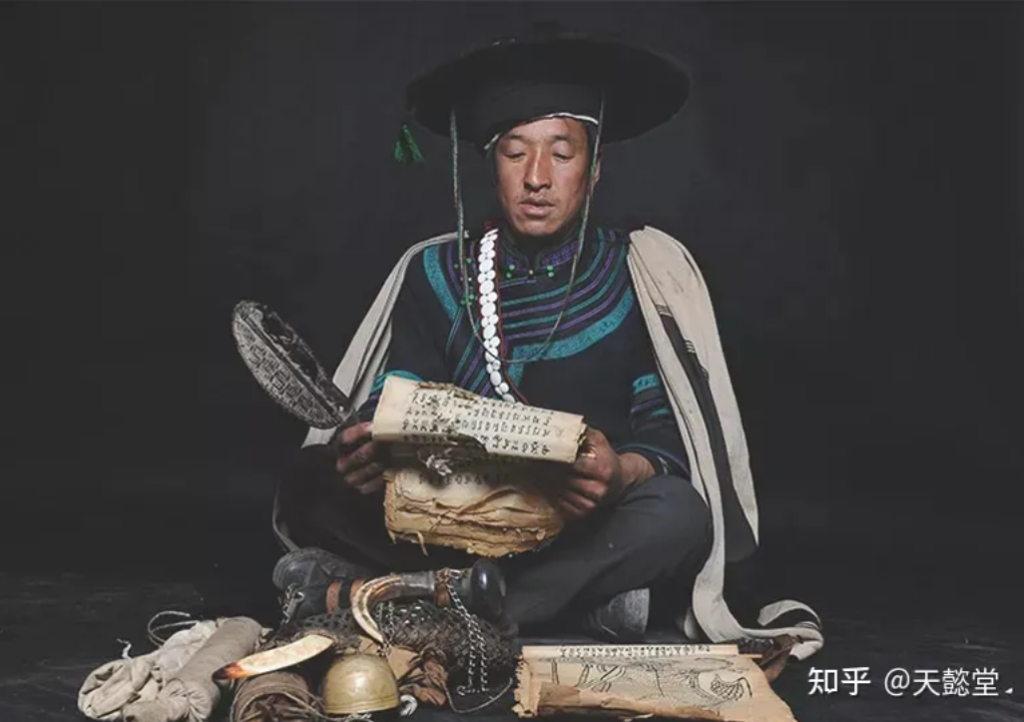

Even though it is well known that religious practices, including divination, are tightly controlled in China, there are still many practitioners among both the Han majority and especially ethnic minorities who practice it openly and privately. This is especially true of the Bimo shamans of the Yi minority, who have mastered various types of divination that are an indispensable part of their daily lives.

Even though the Yi are one of the largest ethnic minorities in China with a total population of more than 9 million, their traditional belief of Bimoism can be considered to be one-of-a-kind religious/shamanic practice that is still popular today. Bimoism can be characterized as belief in ancestral spirits, totems and various nature deities with Bimo being not only the figurehead of the Yi religious and cultural life but also a poet and a theorist of literature. What makes Bimoism special is the frequent use of non-dogmatic sacred scriptures that are tailored to every ritual or divination practice that Bimo is invited to perform. Even though Bimoism is considered a practice of shamanism, it differs from the classical Siberian model by the use of scriptures as the shaman’s main tool of the trade and a medium for transferring cultural and religious knowledge. The process of preserving the sacred and ritual scriptures requires a very thorough preparation and apprenticeship.

In this vast array of sacred scriptures, mantic or divination texts are used very frequently and include various types of practices ranging from astrology to divination according to the 28 houses – a Chinese constellation system in which the moon orbits the earth, worship of plants and celestial deities. It is common for the Yi to also use sacred scriptures while performing divination with various parts of the chicken–tongue, ribcage, femur and egg. The Yi believe that the chicken has the capabilities of seeing spirits and the future.

“The Great Book of Comprehending Mysteries” is one of the largest divination corpuses that has been translated from Yi into Chinese and is still used in the province of Guizhou. It includes an amalgamation of both Yi and Han-specific divination techniques that are employed during minor and major life events such as: childbirth, prognostication of one’s destiny, building a house, going on a journey, determining the compatibility between husband and wife and even between the animal and its master.

Even though the translation and editorial work has been finished at 1982, however, the one thing that this corpus is lacking is a hermeneutic analysis or exegesis that provides an insight into oftentimes mysterious and incomprehensive textual, cultural, religious and illustrative references mentioned in the book as well as the rituals that are left unexplained. For the “Great Book of Comprehending Mysteries” it is common that in case of a bad prognostication it is necessary to perform a ritual, such as: exorcism, purification, healing of one’s birth star, planting a new tree of life, bringing sacrifices and libations to ancestral spirits and various deities to avoid the negative consequences. Rituals are an indispensable part of the Yi religious life.

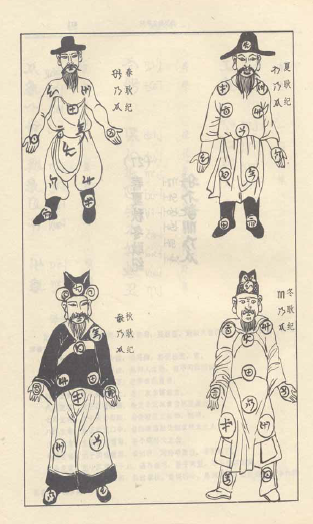

Illustration of the Gengji of four seasons who is the mythical ancestor of the Yi

Illustration of the Gengji of four seasons who is the mythical ancestor of the Yi

My lecture on the 27th of June was dedicated to exploring various divinatory practices mentioned in the first tome of the “Great Book of Comprehending Mysteries” – “Shu She” or also known as the “Golden Book”. In this lecture I concentrated my attention on providing explanations on the rituals required to perform in case of a bad prognostication. The “Golden Book” encompasses a large variety of mantic practices that can be subdivided into auspicious and inauspicious prognostications that require certain rituals to get rid of the negative influence. It is important to note the fact that the “Great Book of Mysteries” is used in Guizhou and the ritual practices can differ from province to province and even from clan to clan, thus it was crucial to use secondary literature on religious rituals that were common only for the province of Guizhou. Owing to the fact that the book has more than 2000 pages, it was not possible to analyze a large part of the divination corpus but only to give an insight into several different mantic practices, such as: astrology, prognosticating the condition of one’s tree of life, prognostication of destiny according to celestial beings and holy ancestors etc. Even though the research emphasized the area of religious practices, namely: the importance of rituals in the Yi society, it is undeniable that not only this divination corpus but also other Bimo religious scriptures are a part of cultural heritage with a long-standing tradition and history that is still preserved nowadays and requires further research, fieldwork and face-to-face interviews with Bimo shamans of Guizhou in order to obtain more precise data which will be the next stage of my research in the nearest future.

The function and Place of Bimo Culture within Historiography

As mentioned at the outset, although there is strict control of religious practices in China, this does not mean that freedom of belief and interest in them have diminished.

#

Aleksandrs Simons received his PhD in Comparative and World Literature at Beijing Language and Culture University (2017). He researches the influence of environmental philosophy and ecocriticism in the literature of ethnic minorities and the preservation of ethnic minority intellectual culture and religious practices in China, focusing mainly on the Yi minority. He was a visiting fellow at IKGF (October 1, 2022-June 30, 2023), where he researched “The Great Book of Comprehending Mysteries” and its significance for the Yi of Guizhou.

___

CAS-E blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by CAS-E on August 14th, 2023.”

The views and opinions expressed in blog posts and comments made in response to the blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of CAS-E, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated.

___

Image credits: © Sichuan Minzu Chubanshe Volume 2 of the Blockprinted Series in Cuan Script, page 878, 1986

© 蒋志聪 Original source: 《普洱学院学报》(Journal of Pu’er University) 2017.2